Everything You Need to Know About Steel Swords

What’s in this article?

Steel swords have a long history and have evolved in response to changing demands on the weapon. However, steel isn’t all created equal—different types of steel have characteristic properties that contribute to the qualities of sword blades.

We’ve compiled a guide on choosing the best steel swords, from the type of steel and its alloys to their construction and uses.

Iron vs. Steel

Pure iron is relatively soft, wears quickly, does not hold an edge well, and has little resistance to bending. On the other hand, steel is a combination of iron and carbon, which makes the soft metal resistant to wear and bending.

Iron with carbon as its primary alloy is often referred to as carbon steel, which most sword blades are made from. As a rule of thumb, the higher the carbon content, the harder the steel will be and the better the steel sword will perform.

Different Types of Steel for Swords

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon, which hardens the softer metal. Some also consist of other elements like chromium, silicon, and manganese to improve the properties of steel blades. In selecting steel swords, you may encounter 1095, 1045, 5160, and such.

Each steel type is usually represented by a 4-digit code. The first digit represents the primary element in the alloy, while the last two digits indicate the carbon content. Hence, 1xxx stands for carbon steels, 5xxx for chromium alloy steels, and 92xx for silicon-manganese alloy steels.

Here are the most common steel types you’ll encounter in sword blades:

1. Plain Carbon Steel

The carbon content of steel changes its properties. Low-carbon steel has less than 0.30% carbon, while high-carbon steel contains carbon usually greater than 0.80%. When heat treated, high-carbon steel swords have good hardness and wear resistance. Generally, a high-carbon steel blade is much tougher and more elastic than low or medium-carbon steel.

Medium Carbon Steel

Low-carbon steel is not suitable for sword blades as it cannot be hardened properly. On the other hand, medium carbon steel, especially those with at least 0.50% carbon content can be quenched and tempered. Some marketing folks refer to steel blades with more than 0.50% carbon content as high-carbon steel. Opinion varies, but half a percent is hardly high by definition.

1045

The 1045 medium carbon steel, with about 0.45% carbon content, would be suitable for sword blades when properly heat treated. It is also more resistant to rust and corrosion compared to higher-carbon steel. However, it is relatively soft and will dull quickly. Still, it is inexpensive and makes a good training sword for beginners.

1060

Composed of 0.60% carbon, the 1060 medium carbon steel is harder than the 1045 and can take a sharper edge. Many consider it the perfect compromise between hardness and flexibility. With proper heat treatment, it makes a decent choice for steel swords. However, it is less resistant to corrosion than lower-carbon steel.

High Carbon Steel

The high carbon content gives the steel its strength and hardness, so high-carbon steel blades retain sharper cutting edges. However, they do not have added elements to make them corrosion-resistant and can stain and rust easily if not cared for.

1095

The best-known high-carbon steel is 1095, which consists of 0.95% carbon. However, a higher carbon content makes a steel sword more brittle and unforgiving when wielded improperly. When heat treated, it can be more resistant to chipping. Many swords, machetes, and kukris have high-carbon steel blades.

2. Alloy Steels

Alloying elements other than carbon can produce qualities not possible in plain carbon steel blades. Some of these elements are silicon, manganese, and chromium. They can either make steel swords more resistant to wear and corrosion or improve their toughness, hardness, and strength.

The most common types of alloy steels for swords are 5160 and 9260. They are sometimes referred to as spring steels as they can retain their original shape after bending or twisting. Spring steels also don’t need frequent maintenance.

5160

The 5160 spring steel is basically a 1060 medium-carbon steel with added chromium, strengthening the steel blade and making it more resistant to corrosion. It is flexible and resists heavy shocks, making it ideal for medieval swords, rapiers, kukris, big Bowie knives, and others where a larger flexible blade is needed.

52100

The high carbon content of 52100, about 0.98 to 1.10%, results in a very hard sword blade and can retain a sharp edge. When properly heat treated, it can be the perfect combination of toughness and hardness. It is commonly seen in hunting knives but less popular for swords due to its complicated heat treatment. Still, some custom sword makers use this type of steel.

9260

The 9260 spring steel is a silicon-manganese alloy. Manganese reduces the brittleness of a sword blade and makes it more resistant to wear and corrosion. On the other hand, silicon improves its strength and hardness, making it more resilient against lateral bends and allowing more flexibility compared to blades made from 5160.

3. Stainless Steel

Stainless steel has a high chromium content, usually more than 12%, making it highly resistant to corrosion. While it works well for small blades and knives, it is not suitable for swords. For blades longer than 12 inches or 30 centimeters, the grain boundaries between the chromium and the rest of the sword blade weaken and easily break. Swords with stainless steel blades are generally only suitable for decoration.

How to Choose the Best Steel Sword?

Steel swords are designed to work in different ways, and certain steel types can make some blades better than others. It matters to opt for a steel type suitable for the sword and practice.

Here are the factors to consider when choosing a steel sword:

Metal and Construction

Steel swords must be hard and tough enough to resist bending and fracturing while retaining a sharp cutting edge. However, hardness and toughness often work against each other, so finding the appropriate balance is an important consideration. Does your steel sword have to hold an edge for a long time, or must it be tough and flexible?

However, steel swords used in tameshigiri or test cutting practice must have proper tempering to withstand powerful impact. Generally, battle-ready swords are made from high-quality carbon steel blades, heat treated, and have full tangs. However, steel swords used in Historical European Martial Arts or HEMA must have unsharpened, flexible blades.

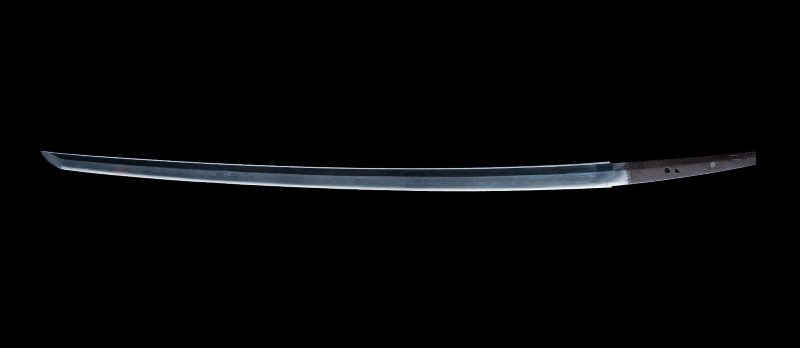

Blade Appearance

Sword blades greatly vary in shape, depending on the sword type and function. While Japanese katana swords and sabers have curved blades for slashing, rapiers have a narrow, sharp tip for thrusting. Some swords also have flame-shaped blades, especially the German great sword zweihander.

Some swords are also valued for the artistic qualities of their blades, especially Japanese swords with distinctive hamon or temperline patterns. Some historical swords from the Islamic world often had damascus steel blades with beautiful watery patterns. The so-called damascus steel swords today replicate the appearance of these swords but are not of the same construction.

Size and Weight

Steel swords greatly vary in length, though long swords have blades usually more than 60 centimeters or 23 inches. Historical swords used in combat were lighter than most people think as a sword that is too heavy would be difficult to lift and swing. Most swords weighed less than 4 pounds, though great swords usually weighed more than 5 pounds.

Sword Mounting

Steel swords used for test-cutting practice must also have functional sword mountings, which can be as plain or as fancy as one wishes.

Hilt

The grip should feel comfortable and provide a secure grip on the sword. Grips vary from wood, horn, leather, wire wraps, ivory, and so on. The pommel often serves as a counterbalance to the blade and prevents the sword from slipping out of hand.

Sword Guard

A sword must have a functional sword guard to protect the hand, though designs vary in different swords. While European medieval swords often had a cross guard, Japanese swords had a disk-shaped or four-lobed tsuba, usually with decorative designs. Rapiers also varied from swept-hilt to cup-hilt guards.

Scabbard

Blunted steel blades can be stored in a leather scabbard or sheaths, but swords with sharp edges must be stored in a wooden or metal scabbard, sometimes with a metal chape to protect its end.

Most Popular Steel Swords in History

Different centers of sword production provided metal of various sorts, so swords also varied in steel quality and construction.

Here are some of the most popular swords in history and the quality of the steel they were made from.

1. Roman Gladius

Most recognized for its large, spherical pommel and double-edged blade, the short sword gladius was one of the typical weapons of the Roman legionary. However, there was no centralized control of Roman weaponry at the time. In the Republican period, sword manufacture was likely outsourced to civilians, though by the Imperial period, the Army manufactured the swords.

The Roman gladius utilized iron and steel of varying carbon content. Most blades had high carbon steel edges welded onto an iron core for flexibility and strength. However, other historical examples were made of medium carbon steel throughout and not quenched. Some sword blades even had a layer of steel wrapped around an iron core, while others had harder cores and softer edges.

2. Viking Swords

Some Viking swords had blades made from a single piece of metal, while others had pattern welded blades constructed from several bars of iron or steel. The pattern welding technique was once thought to provide the best combination of hardness and flexibility for a sword blade, where different alloys with different qualities complemented each other.

Unfortunately, pattern-welded blades were inferior to those made from a single piece of metal, as the technique produced weaker blades, especially on the weld joints. Pattern welding was in practice in northern Europe long before the Viking Age, but the Vikings continued to use it for high-status weapons, as it created decorative patterns on sword blades. However, it was expensive, time-consuming, and impractical, so it became rare after the 9th century.

Some Viking swords, especially the Ulfberht swords, were made from crucible steel, known as wootz steel or damascus steel. These blades were of high quality and were unknown in the west at the time. They were likely imported from the Islamic world, as there was an extensive trade of crucible steel from Central Asia to Scandinavia.

3. Japanese Swords

Samurai swords, especially the long sword katana and short sword wakizashi, are most recognized for their curved blades, but their qualities and properties depend on the steel they were made from. The tamahagane is high-carbon steel produced in a traditional Japanese smelter called tatara, and it is very tough, allowing the sword blade to bend without fracturing.

Due to the tamahagane composition, the steel can be hardened through heat-treating, creating the distinctive hamon or temperline pattern, which Japanese swords are known for. The tamahagane also reveals all artistic details on Japanese blades, including the jigane and jihada or the steel surface texture and pattern.

The Japanese developed their smelting method in the 5th or 6th century when steel swords first appeared in Japan. The tatara process reached its most advanced stage by the 17th century during the Edo period and the beginning of the Meiji period. Today, Japanese swordsmiths still practice their craft and create katana swords and tanto daggers from tamahagane.

Eastern Steelmaking vs. Western Steelmaking

The practice of steelmaking in different parts of the world resulted in distinctive characteristics of steel swords made there. Whatever the method, medieval steel varied in quality, due to a lack of process control and measuring equipment and could not match the quality of modern steel.

In India, Persia, and Central Asia

Steelmaking in the region used the crucible process, in which the steel was produced by heating pieces of iron with materials rich in carbon in closed crucibles. The so-called crucible steel had a very high carbon content and was used in sword blades. Some steel of this type also found their way to Europe by the early Middle Ages.

The famous damascus steel or wootz, with a watery pattern on the blade surface, was a result of controlled cooling and forging. Wootz steel was exported to centers of arms manufacture, such as Damascus, where swordsmiths forged them into sword blades. It remained popular until the 19th century in Iran, India, and Central Asia.

In China

Steelmaking in China utilized a blast furnace, where pieces of iron were melted to form pig iron or cast iron, which had to be refined into wrought iron or rarely steel of moderate quality. Some Chinese swords from the pre-Han period were produced from cast iron, though others were of low or medium-carbon steels.

In Europe

In early medieval times, smelting iron ore produced bloomery iron. The bloomery process used stone or clay furnaces, where pieces of iron were left until more carbon was absorbed. The properties of high-carbon bloomery irons are similar to modern carbon steels.

Early European swords, like Celtic and Roman swords, had steel edges forge-welded onto an iron core to provide a combination of strength and flexibility in a blade. This technique is known as piling.

From the 5th to 10th centuries, the process also produced pattern-welded blades, with a variety of decorative patterns, depending on how the pieces of metal were piled and twisted. However, pattern welding was an advanced technique during the time and used in the Roman long sword spatha and Viking swords—but not in the Roman short sword gladius.

Eventually, European swords made of a single piece of steel displaced pattern-welded swords. The sword blades of rapiers, great swords, and hand-and-a-half swords were often of homogenous steel, which had been folded and forged into shape, then hardened by slack-quenching and tempering.

In Japan

Traditional Japanese steelmaking resembles European methods rather than Chinese ones. Swordsmiths use the high carbon steel known as tamahagane, produced from the tatara furnace, a very large bloomery. The tamahagane is smelted from satetsu or iron ore in sand form. When the satetsu is smelted in the tatara, the resulting steel has a very high carbon content, and the swordsmith refines it to make a practical and functional sword.

More than that, Japanese swordsmiths harden only the cutting edge of the sword by coating the blade with clay before the heating and quenching process. The clay coating is very thin on the cutting edge and relatively thick on the body of the blade. It allows the edge to cool quickly while slowing down the rate of cooling on the other parts of the blade. As a result, the sword would have a hard edge and a relatively soft body that remains tough.

If the entire blade is hardened, it would only be very brittle and break upon use. Generally, a properly-made Japanese sword has three types of steel: a hardened cutting edge or hamon, the hard high-carbon steel that forms the blade surface, and the soft steel core. The softer steel core at the center of the sword serves as a shock absorber to prevent it from fracturing.

Uses of Steel Swords in Modern Times

Apart from collection, steel swords remain significant in weapons training in martial arts. They are also common in historical re-enactments, modern recreations of medieval battles, and theatrical swordplay.

In Martial Arts

Martial artists, who train in Japanese swordsmanship, use steel swords with sharp blades in tameshigiri or test cutting practice, which allows them to apply the proper cutting strokes and sword techniques. The typical targets are bamboo, tatami mats, water-filled bottles, and even rounded fruits. For non-lethal practice, they also use other training swords like bokken and iaito.

In Historical European Martial Arts or HEMA, practitioners use steel swords with flexible blades that bend in the thrust. These unsharpened swords include arming swords, longswords, great swords, rapiers, and military sabers. Sometimes, practitioners utilize wooden sword wasters, especially messers, dussack, sabers, and hangers for forms using one-handed swords.

In Historical Re-enactment

Several performances portray Roman or Viking combat, utilizing blunted gladius and Viking swords. For safety purposes, many re-enactors prefer wooden sword wasters to steel swords. Modern reproductions of these swords also feature non-steel blade material, including polypropylene.

In Theatrical Swordplay

Steel swords appear as cinematic props, but using live blades is only done in controlled circumstances. Some blunt steel swords are suitable for theatrical combat or fight scenes, but many prefer blades with relatively smooth and rounded edges—not squared that could fly off as metal splinters.

Steel swords are heavy, so some also use lighter aluminum sword blades. The latter can look like steel, is easier to control, and allows faster movements. However, aluminum is not suitable for impact like carbon steel blades. In films, many background fighters use bamboo blades covered in a metallic film, hard rubber swords, or polypropylene swords.

In Cosplay

Swords are popular weapons in anime, comic books, video games, and films, making them the favorite standard props of cosplayers. Many play the role of their favorite character, from a samurai to a ninja and a medieval warrior. However, most pop culture events do not allow steel swords, so many prefer wooden or polypropylene weapons. Some events allow blunted steel swords as long as they remain in scabbard and zip-tied or fastened to a costume, so they can’t be drawn.

Conclusion

Steel swords are not created equal and each type has its own pros and cons. Today, steel swords are an efficient training weapon in martial arts and popular in historical re-enactment and theatrical swordplay. Many collectors even value them as objects of art.