Shingane: The Core Steel of the Blade

What’s in this article?

Japanese swordsmiths mastered merging the conflicting qualities of steel—hardness and flexibility—into a high quality blade. The shingane refers to the core steel, which is softer and more flexible than the rest of the blade. It has a significant role in the blade’s construction, contributing to the functionality and efficiency of the sword as a weapon.

Let’s explore the properties and function of a shingane, its use in different blade constructions, and how it makes a sword blade effective.

What Exactly Is a Shingane?

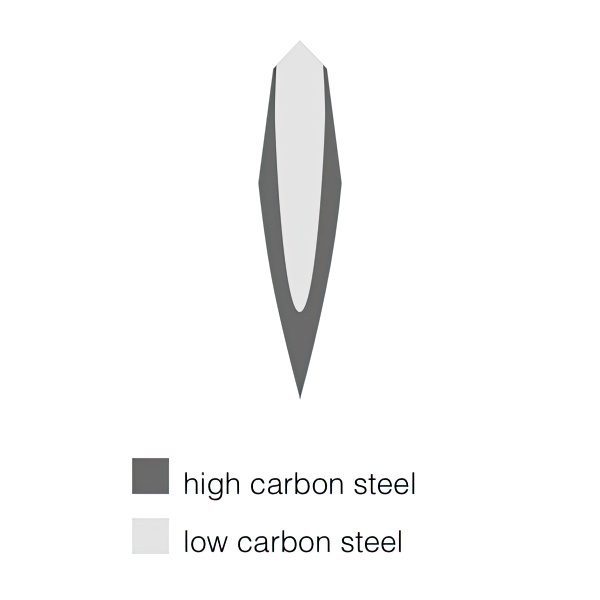

The Japanese term shingane (心金/心鉄) literally means core steel. Long and short swords are usually made of a combination of a softer, low-carbon core steel, the shingane, and a harder, high-carbon outer steel jacket that forms the blade’s surface, the kawagane.

A functional and efficient sword had to be hard enough to retain its sharp cutting edge while being flexible to withstand impacts. However, hard steel is brittle and prone to chipping or cracking under stress.

As a solution, Japanese swordsmiths incorporated a core of soft steel within the hard steel jacket. The shingane functions as a shock absorber to prevent the forged blade from cracking or breaking under hard blows.

The Shingane in Various Blade Constructions

A properly-made Japanese sword blade is constructed from different types of steel. The shingane, a softer steel core with a lower carbon content, is often used. However, there are various ways to create a sword blade, and different groups of swordsmiths use various methods.

1. Kobuse Gitae

A kobuse gitae is a blade construction where the shingane is wrapped in a high-carbon steel jacket, the kawagane. Kobuse (甲伏せ) means armor covered, while gitae (鍛え) means forging. It is the most common form of blade construction for Japanese swords. It is commonly seen on Bizen blades and those of other schools during the Sengoku “Warring States” period when constant warfare required more efficient sword production methods.

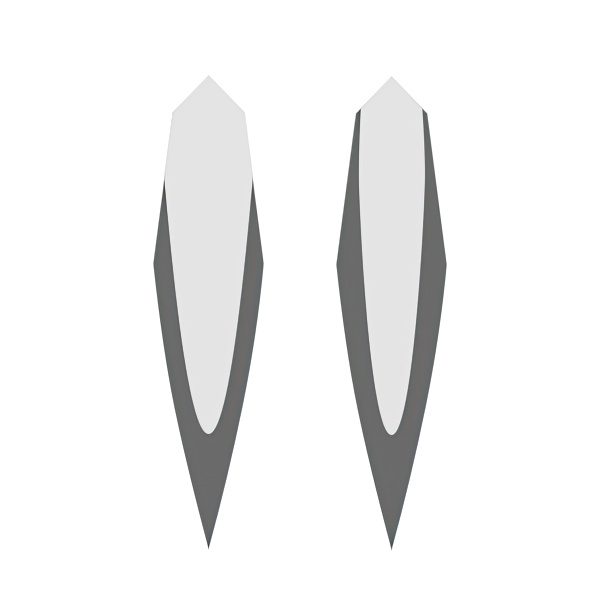

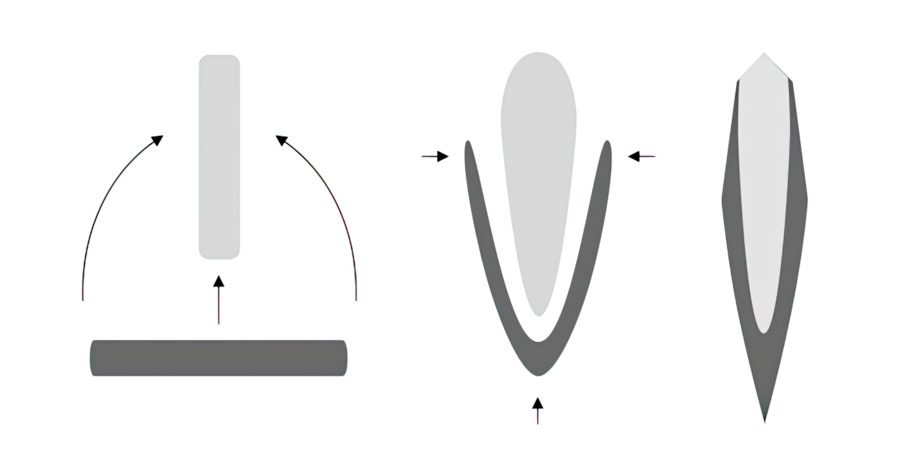

In the kobuse construction method, the shingane is sandwiched between a U-shaped piece of kawagane, and then, the two pieces are welded together. It is less labor-intensive than the more elaborate blade constructions. It can make a strong sword with a hard cutting edge and a more resilient body when done correctly. However, too much polishing can wear down the outer steel jacket and reveal the core steel.

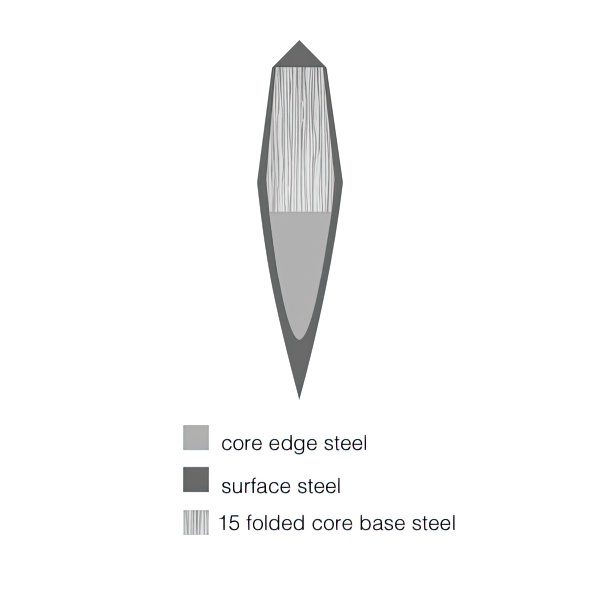

Shin Jugomai Kobuse-Gitae

A variation of the kobuse blade construction, the shin jugomai kobuse-gitae uses two types of core steel: shin-jitetsu (core base steel) and shin-hatetsu (core edge steel). The term shin can be interpreted as short for shingane.

The shin jugomai kobuse-gitae (真十五枚甲伏鍛え) means true 15-folded kobuse forging. It implies that the blade is constructed through the kobuse method using 15-times folded steel. The shin-jitetsu (core base steel) is folded 15 times to soften it, hence the name.

This type of blade construction likely started with swordsmith Omura Kaboku during the Kanbun period, from 1661 to 1673. Swordsmith Suishinshi Masahide also made blades in this method, and other Japanese swordsmiths continued using it until the 19th century.

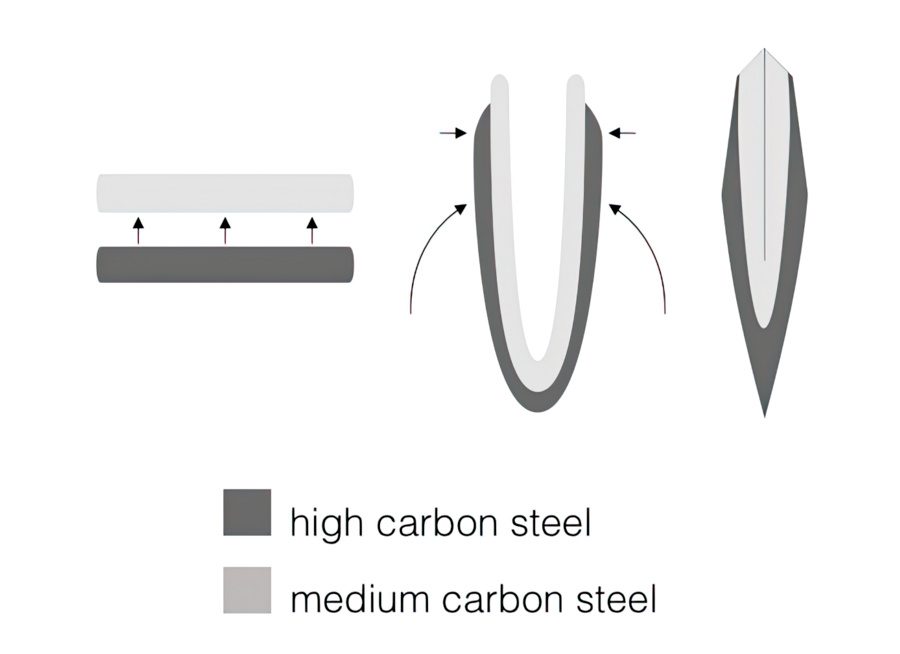

2. Makuri Gitae

Similar to kobuse gitae, the makuri gitae is another method to create a blade with a softer core (shingane) wrapped in a steel jacket (kawagane). Makuri gitae (捲り鍛え) means roll-in forging. It is a common blade construction in antique Japanese swords and Bizen blades.

In the makuri construction method, a plate of shingane is placed on a plate of kawagane, and the two pieces are folded in half. Although a little different, this method achieves the same result as the kobuse gitae, making a strong sword with a hard, durable blade.

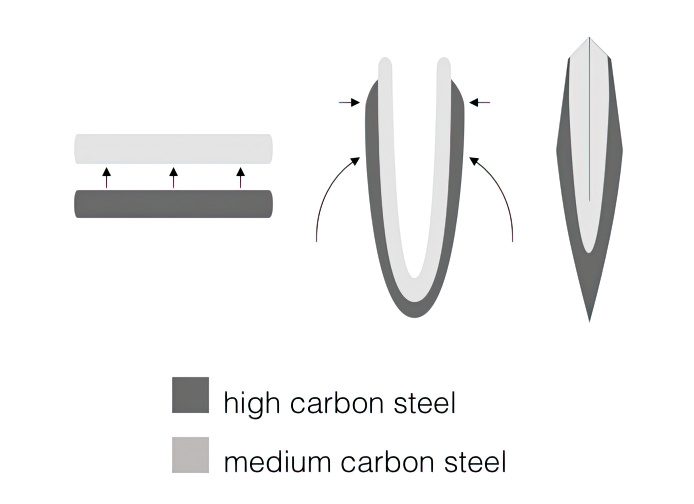

3. Honsanmai Gitae

A honsanmai gitae (本三枚鍛え) uses three types of steel: the shingane (core steel), the kawagane (outer steel), and the hagane (edge steel). Technically, the shingane is placed between the two outer pieces of kawagane. Then, the hagane is placed below and forged to become the blade’s cutting edge.

The three layers (sanmai) of steel are also of varying hardness. The shingane (low carbon steel) is softer, the kawagane (medium to high carbon steel) is harder, and the hagane (high carbon steel) is the hardest. The portion where the kawagane and hagane meet may feature kinsuji (golden lines) and sunagashi (flowing sand) on the blade’s surface.

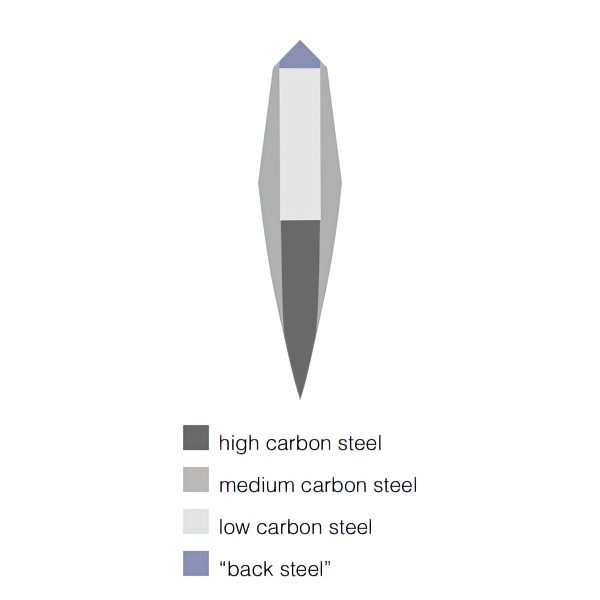

4. Shihozume Gitae

More complicated composite steel bars use four or more different types of steel for the core, the sides, the cutting edge, and the back. The shihozume gitae is similar to honsanmai gitae but has an additional section of back steel called munegane.

Shihozume gitae (四方詰め鍛え) translates as four sides packed forging. This type of blade construction involves layering low-, medium-, and high-carbon steel. Still, the softest is the core steel (shingane), and the edge steel (hagane) is the hardest. Some swordsmiths will make a medium-hard steel for the back of the blade.

Facts About the Shingane

Japanese swordsmiths discovered that using just one type of steel was inadequate for creating exceptional sword blades. Unlike the earlier swords without core steel, samurai swords constructed with shingane rarely warped or broke in combat.

Early Japanese swords lacked shingane or core steel.

Old swords from the Koto era, from about 1000 to 1600, utilized a single type of steel, usually medium to high carbon steel. This basic blade construction is called maru gitae (丸鍛え), meaning whole forging. The differences in blade hardness, in the blade’s body and cutting edge, were achieved through heat treatment applied on the finished blade.

Japanese daggers and small knives usually do not have core steel.

The Japanese long sword katana and short sword wakizashi are made of a composite structure, often three types of steel: core steel (shingane), outer steel jacket (kawagane), and edge steel (hagane). However, tanto daggers and small knives, such as utility knife kogatana, are made from a single piece of steel.

The kawagane serves as the surface of the blade.

As an outer steel jacket, the kawagane forms the blade surface. It features the jihada or the visible surface pattern of Japanese blades. In some blade constructions, such as the kobuse gitae, the kawagane also includes the sharp cutting edge, which will be hardened to form the hamon. This process of creating a hamon (temperline pattern) by heating and quenching the blade is called yaki-ire.

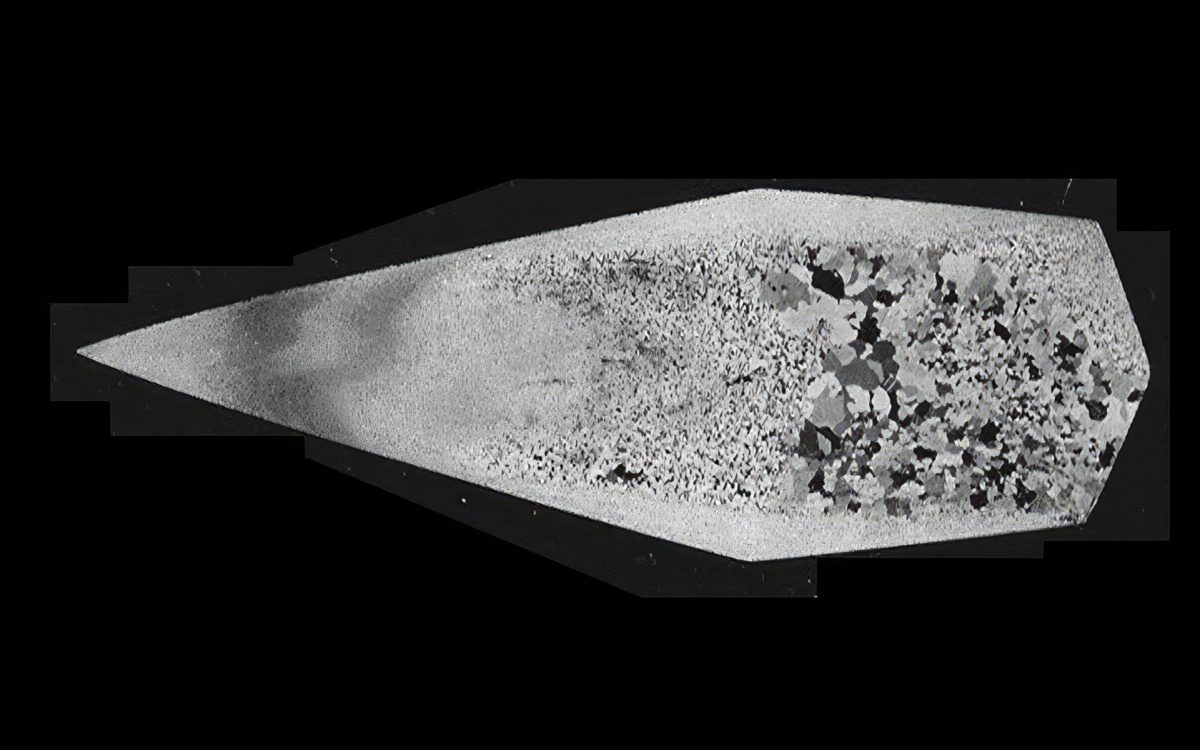

Too much polishing can expose the shingane.

The polishing work removes metal from the blade, and too much polishing can remove the kawagane from the blade surface, exposing the core steel, the shingane. Swords in this condition are considered “tired.” When the shingane comes out into the hamon (temperline pattern), the pattern of the hamon becomes obscured.

The shingane is often made of tamahagane.

Japanese swordsmiths produce the core steel from tamahagane, the steel from the traditional tatara smelter using iron ore in sand form. The hocho tetsu (iron used for common household knives) was sometimes used for the shingane. However, the sen tetsu (pig iron) had been discarded in sword forging as it was considered below standard.

Some mass-produced swords had thick shingane.

In the Muromachi period, from 1338 to 1573, some swords were mass-produced and called kazuuchi-mono, meaning made in large numbers. They were made with thicker shingane (steel core) to economize on valuable material, such as the tamahagane. The Osafune swordsmiths of Bizen province and the Seki smiths of Mino province mainly produced them. Due to the thicker core steel, their shingane easily appears after polishing.

The variations in constructing a Japanese blade show how sword making schools evolved independently over the centuries.

Japanese swordsmiths experimented with many different blade construction methods in hopes of rivaling the best swords from the past. In the Shin-shinto era, about 1790 to 1876, Edo-period swordsmiths used complex welding schemes to recreate the lost secrets of the Koto masters.

Conclusion

The shingane is the soft steel core found within Japanese sword blades. It helps in preventing the blade from cracking under stress. By incorporating it into the blade construction, Japanese swordsmiths achieved a remarkable combination of resilience and sharpness, creating efficient swords for combat.