Seppuku: The Japanese Samurai Philosophy of Ritual Suicide

What’s in this article?

Seppuku, the ancient Japanese culture of honourable death through ritual suicide, is one of the most famous aspects of Japanese history, and was practiced in Japan from the medieval period right up until the modern day. Also known as hara-kiri, the act was often carried out as a way to die with honor or to restore honor to the family after a shame or defeat which had brought dishonor on a warrior or his family.

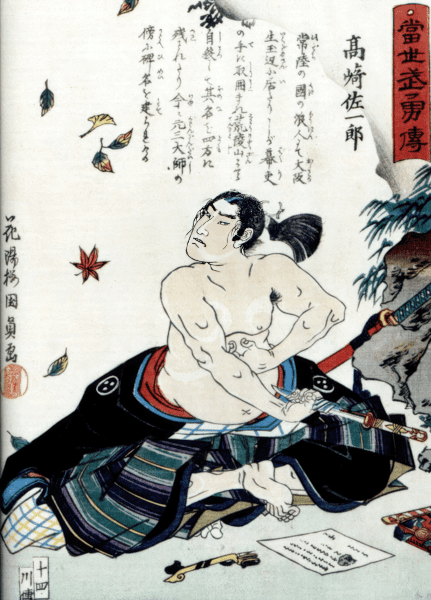

The history of samurai suicide evolved throughout the centuries, but had reached its most elaborate and well-known form by the Edo period (1600-1867). Generally, the ritual suicide involved the warrior or person disemboweling themselves with a short sword, wakizashi or tanto – it is this part which hara-kiri really describes, literally meaning ‘belly-cutting’. After or during the disembowelment, another trusted warrior was to cut off the head of the person committing suicide. The two together; the belly-cutting and the beheading, are known as seppuku.

The Early History of Seppuku

Hara-kiri is first mentioned in Japanese literature in 713 in the record of the legend of Harasaki or ‘belly-slashing’ marsh. The legend tells of the goddess Aomi who, in bitter fury after losing her husband, slashed her belly with a sword and drowned herself in the marsh waters.

This harrowing tale shows that the link between suicidal fury and stomach-cutting had taken root in the sixth or seventh century. This is well over four hundred years before the first historical record of hara-kiri.

Over these centuries, hara-kiri appears to have become associated with martial arts and the samurai warrior. In 1170, the samurai Minamoto no Tametomo committed suicide after a failed rebellion. With a last heroic effort, he let loose a single arrow which sank an entire ship full of warriors before ripping open his belly. After dying, he was later found and beheaded by his enemy in an early, albeit unintentional, form of seppuku.

Tametomo was described as ‘coarse’, ‘ferocious’, and ‘demon-like’; all qualities which suited the more primal and violent ideals of early samurai warriors. This reflects the earlier view of hara-kiri as an act of suicidal fury, as opposed to the more thought-out act of regaining honour that it would become in later times.

In most of the earlier tales of feudal Japan, defeated generals and heroes would only commit suicide through hara-kiri without the beheading; waiting to die in a much more brutal and painful suicidal act than if they had been killed immediately afterwards. This style of hara-kiri usually took the form of making a horizontal cut across the belly, and then a vertical cut through the first cut, forming the shape of a cross and disemboweling the warrior.

Seppuku During the 1500s: The Development of Honorable Death

Around the 1500s, ritual suicide became increasingly premeditated, rather than a spontaneous act of defiance or fury. Seppuku became a form of capital punishment written into samurai codes, or bushido. Bushido was the strict moral code followed by the samurai class. By following bushido, a samurai lived with honor. Interestingly, seppuku was often written into punishment lists as a less severe punishment than confiscation of the katana and, as a result, samurai status. The ritual of seppuku was preferred over dishonor which shows that the link between seppuku and an honorable death was beginning to be formed.

At the same time, in accordance with the bushido samurai code of devoting oneself to your lord, voluntary seppuku by retainer samurai after the death of their daimyo or warlord became common. In 1582 Nishina Morinobu, led a last ditch defense of the Takeda clan against overwhelming odds. The battle has been likened to the last stand of the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae.

After fighting back wave after wave of invaders, it inspired civilians, women, and children to take up arms, causing the defender’s castle to be almost overwhelmed. Morinobu, left with just thirty of his retainers, climbed onto the castle roof, removed his armor and slashed his belly. Upon seeing their lord’s death, each of his loyal retainers killed themselves. Morinobu was buried with full honors by his enemies and was considered by many samurai to have experienced a warrior’s death.

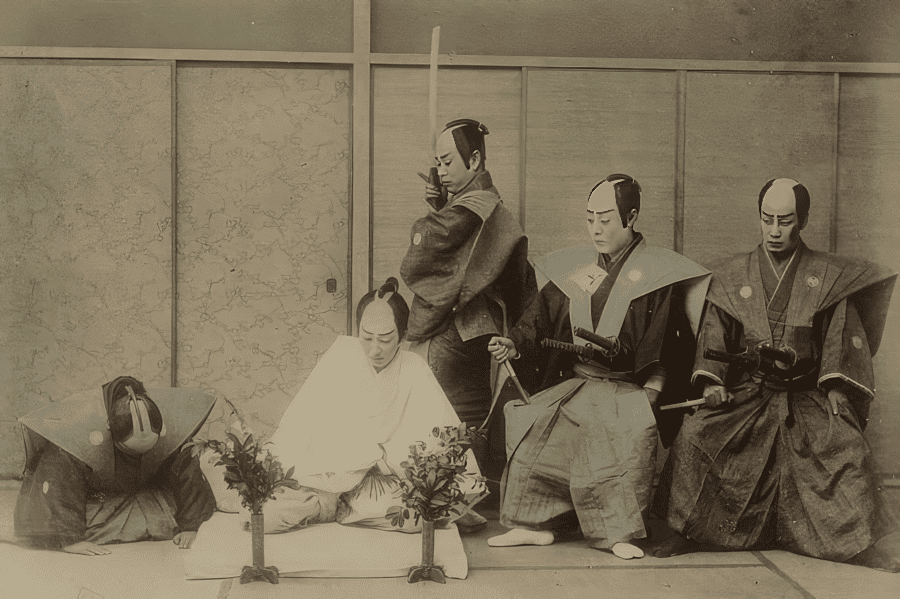

By the late 1500s, a new word became associated with seppuku; ‘kaishaku’. The exact meaning is unclear, but it might be similar to ‘kind assistance’ and refers to cutting off the head of someone who has committed hara-kiri. This compassionate decapitation served as a mercy to quickly end the painful act of belly cutting, turning hara-kiri into the ritual of seppuku in its nearly finalized form.

The beheader, known as the ‘kaishakunin’, would have been a trusted and skilled swordsman and almost always a loyal retainer of the person who is committing suicide. Therefore, the act of kaishaku became an act of ultimate devotion to one’s lord. In the same vein, the samurai who assisted his lord in committing seppuku also had to take his own life, as he could not honorably continue to live after committing such an act.

All these developments resulted in a nearly fully formed ritual of seppuku by the dawn of the Edo period, with all its associations of martial honor and poetic beauty.

The Formalised Ritual of Seppuku

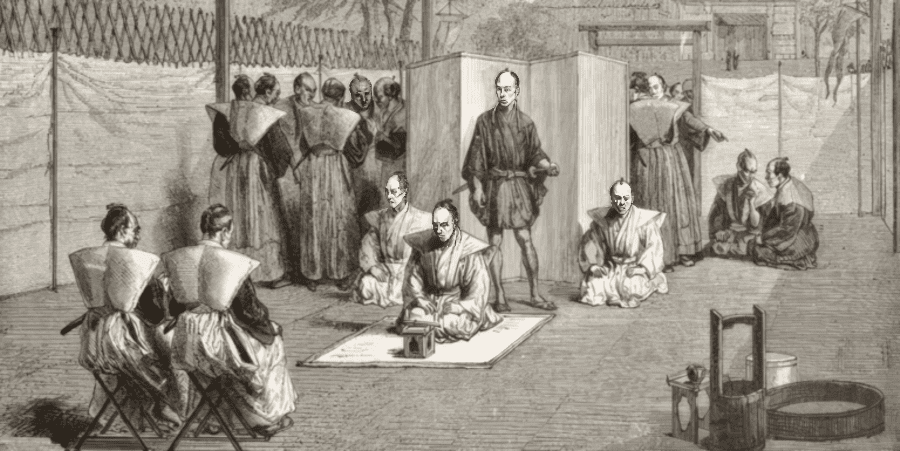

From the 1500s onwards, the ritual of Seppuku became highly formalized, with specific guidelines and protocols written down. The location was prepared according to the rank of the samurai, with tatami mats laid down and curtains hung. Candles were lit and incense burned in order to make the scene less distressing for spectators.

A ceremonial kimono was worn and the weapons used were ceremonial. A knife known as a tanto or short sword known as a wakizashi was used for the hara-kiri. It was also taboo for the kaishakunin to use his own sword for the beheading.

The moment at which the kaishakunin was to strike was agreed beforehand and ranged from the moment the warrior sliced open his belly to the moment the warrior began to reach for his blade, meaning that the warrior was killed before he even performed hara-kiri. This shows how highly ritualized the act had become. The different types of seppuku were also named and categorized.

| Types of Seppuku | Description |

|---|---|

| Ichimonji | A single horizontal cut across the belly |

| Jūmonji | A horizontal cut across the belly followed by a vertical cut in the shape of a cross |

| Hachimonji | Two vertical cuts across the belly |

| Sanmonji | Three horizontal cuts across the belly |

| Tachi-Bara | A stomach cut performed in a standing position |

| Oi-Bara | Suicide immediately after acting as kaishakunin for one’s lord or daimyo |

| Kanshi | Suicide committed in protest of another’s actions |

| Kage-Bara | A cut across the belly, which is then concealed and then revealed to others with dramatic effect, usually as a form of Kanshi or to prove a point |

Seppuku During the Edo period

During the relative peace of the Edo period, there was far less opportunity for securing an honorable death through battle or seppuku. However, samurai continued to carry out seppuku after the natural death of their lord, which was known as ‘junshi’.

Seppuku continued to be used as a punishment by the Emperor against those samurai who had committed crimes such as killing a civilian, theft and corruption, or brawling. This is a continuation of the high standards of honor upheld by samurai families. Any of these crimes brought dishonor on the samurai, for which the only alternative was seppuku.

That seppuku became a punishment for duels and fighting beyond the period contributed significantly to the demilitarization of Japanese people. For a samurai to even draw his sword in palace grounds was considered an insult to the emperor and resulted in mandatory seppuku. As military battles became less frequent, seppuku began to be used as a response to shame in civilian affairs as well.

Just at the close of the Edo period, the Satsuma rebellion of 1877 against the Meiji government came, after military reforms which made the samurai class obsolete. Disaffected samurai fought to reinstate their power as a noble military elite, led by Saigō Takamori.

Ultimately unsuccessful, Saigō and many of his warriors committed seppuku before they could be captured. Saigō may have actually died from a bullet wound but was beheaded by his close followers in order to maintain his dignity as a true samurai. This shows clearly the strength of the traditional martial values of honor, heroism and a perfect death which the disaffected samurai were still struggling to uphold.

Seppuku in Modern Japan

The practice of seppuku has continued right up to the modern day in Japan. After the death of the Emperor Meiji in Tokyo in 1912, General Nogi Maresuke and his wife Shizuko committed seppuku in an act of junshi.

The Japanese kamikaze suicide pilots of World War II upheld many traditional beliefs surrounding seppuku, such as death poems and the idea of an honourable death. Numerous military officers committed seppuku in 1945 with Japan’s defeat at the end of World War II.

One of the most famous examples of modern day seppuku was committed by Yukio Mishima, author and nationalist who attempted a coup in 1970 against the government of Japan. Mishima had hoped to return to a traditional Japan which upheld the values and ideology of the samurai and dignity of the emperor. When his coup failed, Mishima and his close followers committed seppuku in a final symbolic act of devotion to his ideals.

From an act of violent defiance and fury to the carefully curated ritual of honor and poetic beauty, seppuku embodies the values of the warrior throughout the history of Japan. The astounding continuity of the ritual illustrates the strength of the values of honor and tradition in Japanese culture right up until the present day.