Oakeshott Type XVIII: The Quintessential Sword of the Middle Ages

What’s in this article?

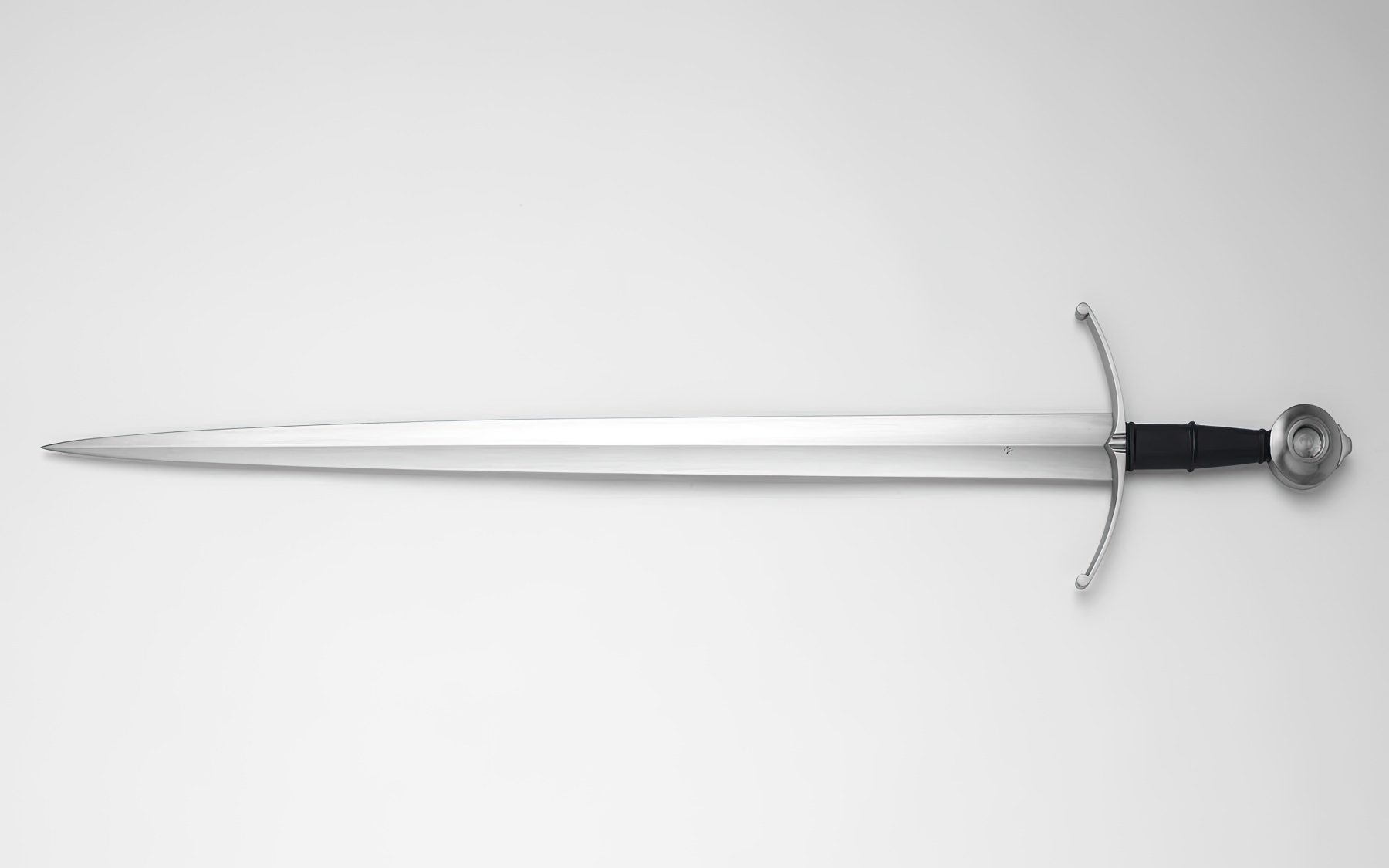

The Oakeshott type XVIII is the ninth European blade type and one of the most popular, effective, and important swords used by the European knights of the Late Middle Ages. It was a successful cut-and-thrust weapon for dealing with plate and chainmail-armored opponents during the early 15th and 16th centuries. The type XVIII often comes to mind when speaking of a double-edged European sword with a cruciform crossguard.

Ewart Oakeshott was a British illustrator and amateur historian with a profound passion for European medieval arms and armor. His primary focus was classifying European double-edged blades in a typology chart called Oakeshott’s Typology. It is based on Oakeshott’s 50-plus years of thorough research and personal collection of antique swords.

In this article, we are going to discuss the Oakeshott type XVIII. We will start by examining its unique blade-defining characteristics and how it was best used. Then, we will explore its many sub-types that follow a general theme but differ in some aspects. We will conclude the article by touching upon this type’s history and some historical antique examples.

Characteristics of Type XVIII Swords

The type XVIII sword of Oakeshott’s typology stands out as a quintessential European sword thanks to its characteristics. These traits are frequently depicted in art and contemporary media but are almost impossible to identify reliably due to inaccurate depictions by medieval artists. Han Talhoffer’s 1467 combat manual, Fechtbuch, shows them in great detail.

Its wide recognition is thanks to its elegant yet simple design that proved highly effective and successful on many battlefields of the Late Middle Ages. While XVIII swords had different variations and sub-types, they all generally had the same characteristics.

Blade

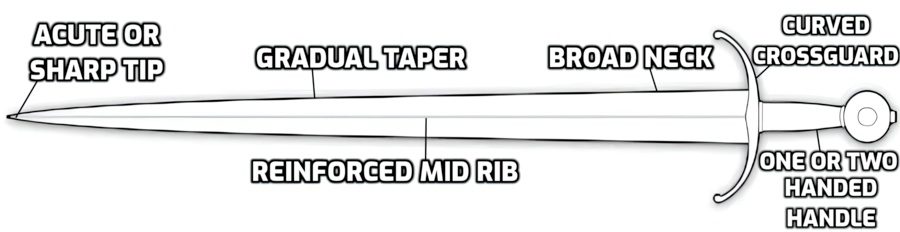

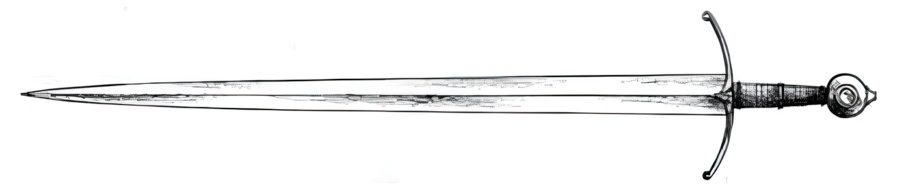

The Oakeshott type XVIII sword had many blade characteristics similar to the previous type XV, the first European medieval thrusting blade. The XVIII is a double-edged, straight blade that was relatively broad at its neck and near the crossguard, tapering to an acute tip. Its blade profile is mostly flat with a diamond cross-section or a well-defined hollow ground form.

A smaller fuller could be found in some sub-types through the blade’s center, but generally, a strengthened, well-defined mid-rib acts as a stiffener. The taper is gradual and light, making a slight convex center of percussion. This made it a powerful thrusting tool with capabilities of cutting as well. The tang underneath the handle was rectangular in design and ended with the pommel.

The difference between type XVIII and type XV blades can be hard to distinguish, but some things separate them, the most visible being the taper, which is much lighter in type XVIII.

Hilt (Guard and Pommel)

The hilt of the type XVIII sword could be one-handed or hand-and-a-half. Some handle designs have a slimmer and longer pommel, allowing it to be used as a two-handed weapon.

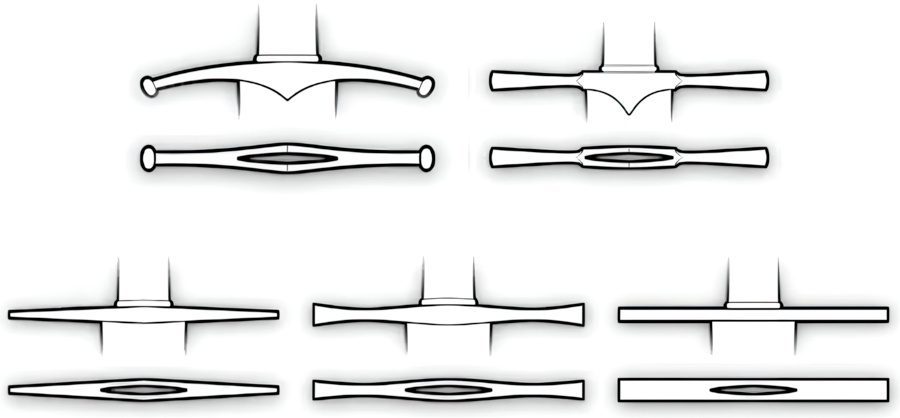

Being one of the most popular 15th-century swords, the XVIII featured many guard designs. The most practical and sophisticated crossguard was a slim, narrowed guard with bent quillons toward the blade.

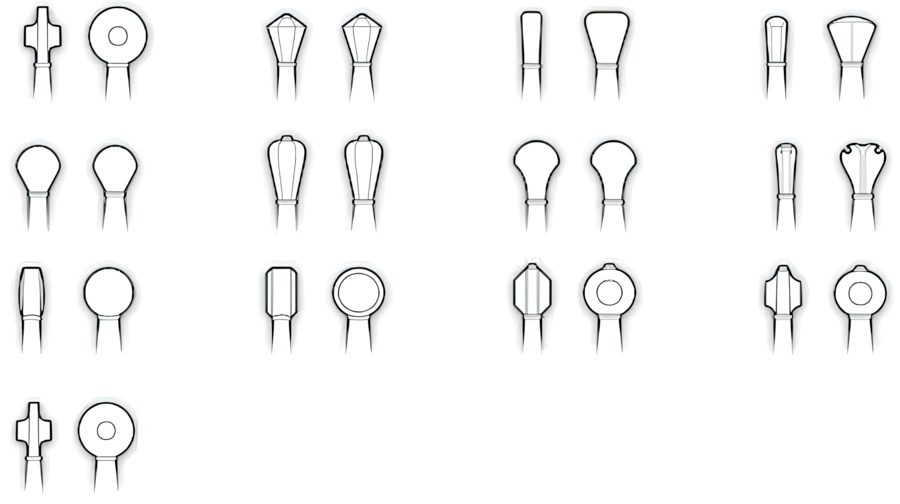

The pommels could vary in design, size, and type from popular pommel shapes of the time. Some of the most frequent were a disc form with broader chamfers that widen at the face and those rounded in design with hollowed-out chamfers with a disc variant. The most common was a scent stopper pommel, which was slim and longer with a wider top or wedge that allowed it to be held with an extra hand.

Size and Weight

The size of an Oakeshott type XVIII varied from sword to sword. The blade’s versatility allowed it to fall between being a long and short length. It could be practical in close quarters or long compact formations and the perfect weight to combat enemies on the battlefield. The weapon’s weight ranged from 2 to 3.8 lbs (0.9 to 1.7 kg) depending on its function or proportions.

The size and dimensions of the XVIII also didn’t follow a standard, but swords that have been discovered had a blade length of 27 to 36 inches (69 to 91 cm) with a hilt that ranged from 3.75 to 5 inches (9.5 to 13 cm), giving it an average length of around 38 inches (97 cm).

Sub-type XVIIIa

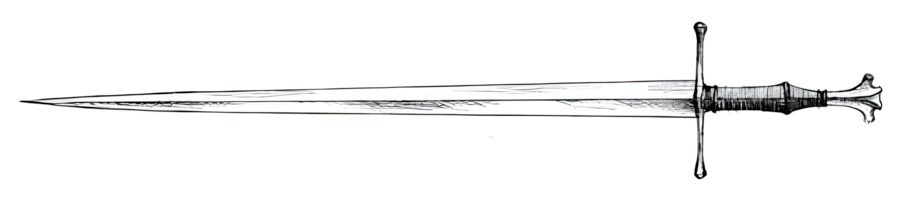

The first group of the many sub-types under the parent type XVIII was XVIIIa, which was almost identical to the main group but differed in the blade profile and the handle. Sub-type XVIIIa had a slender blade that would be more effective when finding the gaps in enemy plate armor. Its grip was slightly larger with a bulge in the middle, making it a primary hand-and-a-half weapon. Its blade could feature a fuller near the guard as well.

This sub-type was a versatile, popular knightly longsword or hand-and-a-half sword used on the battlefields of Europe. The slight decrease in plate armor due to the effectiveness of long-range projectiles in the 15th century increased the weapon’s popularity.

Sub-type XVIIIb

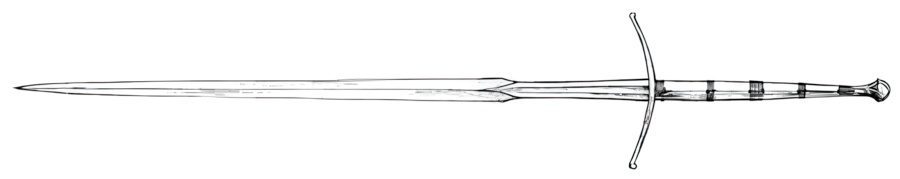

The sub-type XVIIIb is often called a Germanic longsword due to the 15th and 16th-century design from Germany, where the weapon was used throughout the country. The XVIIIb was an adaptable sword used on horseback on the battlefield, carried as an everyday tool, or used in sword training exercises.

Its larger blade length was around 32 to 42 inches (81 to 107 cm). Its blade profile was similar to the parent type with a more slender diamond or hollow ground cross section with a wider center of percussion (where the point makes contact with the target.) The result was an agile and precise cut-and-thrust sword that could be used in quick, deadly offense and defenses.

This Oakeshott sub-type had a large two-handed hilt with a ridge in the middle averaging around 11 to 12 inches (28 to 30 cm) long. It featured similar pommel characteristics, such as a scent stopper or a wheel form with a crossguard that was usually straight.

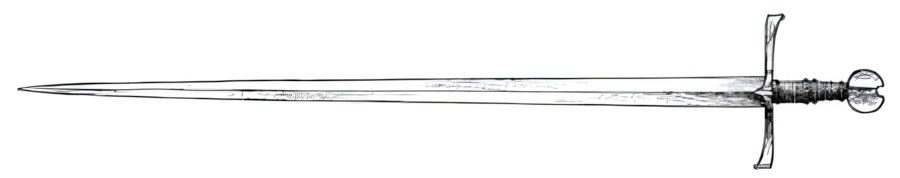

Sub-Type XVIIIc

Type XVIIIc swords were similar to the renowned XVIIIb, with the exception of being slightly smaller, and featured a blade that drew elements from previous cutting swords. One element was the much broader blade base near the crossguard that was wider than two inches (5 cm). That made it a specialized type of weapon that could be used for thrusting thanks to the pointy tip, but it was also an impressive cutting tool.

The type XVIIIc had a long grip with a pronounced bulge in the center. Its sizable pommel was usually rounded, and its crossguard was of the S-shape. The blade was a diamond cross-section with a slightly convex face.

It was a rare type of specialized cutting sword used on the European battlefield, and there remains one physical example today: the Alexandria Sword gifted to the Mamluk rulers of Egypt during the early 15th century as a peace offering. While Oakeshott doesn’t generally use the term “heavy” in his manuscripts, he makes an exception with the XVIIIc, referring to it as a “much heavier” sword, which suggests that the weapon may have weighed significantly more.

Sub-Type XVIIId

Some in the sword community consider the XVIIId a poor sub-type because it shares few characteristics of its parent XVIII type.

It has a smaller one-handed handle, a more slender blade profile, and a fuller running from the guard through the entire blade length. This blade shape is similar to a later-type rapier or side sword that could be used primarily for thrusting but also light slashing against unarmored opponents.

Because the XVIIId is a later sub-type, its crossguard contrasts with attributes of later-type swords. It can have a straight guard or a horizontally shaped S-guard that downturns sharply toward the blade. Some also feature side rings.

Sub-Type XVIIIe

The XVIIIe sub-type is often called the Danish war sword because surviving antiques were mostly found in Northern Germany and Denmark. It was however used outside of these regions as well and could be found in Italy.

It had a narrow, flattened diamond cross-section, ending with a sharp tip. The blade generally tapers more than its parent type and has an unusual fuller or unsharpened ricasso near the hilt, allowing its user to grasp it if necessary.

Its massive hilt can easily be wielded with both hands while featuring a large blade of up to 42 inches (107 cm). The crossguard slims toward the blade with bent quillons, and the weapon’s pommel is long, slim, and pear-shaped.

Uses for the Type XVIII Swords

The Oakeshott type XVIII and its sub-types were versatile longsword weapons that could be utilized for forceful surprise attacks and defenses. They could be used with one or two hands, depending on the type. They were used in large infantry shield formations and for mounted knights. Slashing from above had the added momentum of the speed, and the pommel was ideal for bashing. The XVIII could be used as a primary weapon of a fully plated armored warrior.

Its slender blade profile was effective for thrusts against plate-armored opponents with gaps and slight openings in their armor. The Type XVIII could be half-sworded and navigated as a dagger through these gaps or used for strangling the opponent from behind. It was also adequate for cuts due to the width of its center of percussion, including possibly decapitation or severing a major muscle or ligament through chainmail or brigandine armor.

This cut-and-thrust sword became illustrious because it was adequate and versatile on the battlefield, which made it a hot topic in medieval fencing. It can be seen in a variety of fencing manuals such as Hans Talhoffer’s “Fechtbuch” combat manual of the 15th century. It is also found in other types of Kunst des Fechtens (medieval art of longsword combat) and in modern HEMA (historical European martial arts) training. Due to its adaptability in combat, some call it one of the strongest swords in history.

History and Historical Examples of Type XVIII Swords

With the coming of the early 15th century, the appearance of fully kitted armored warriors was seen on the battlefield. However, they were limited in number and only used by those who could afford them. Along with the success of long projectiles, this weapon made it so there were plenty of lightly armored troops with chainmail or brigandine. There was a need for a more capable thrusting blade that could easily inflict deadly cutting wounds. These factors combined contributed to how the type XVIII came to be.

The XVIII swords were used from the early 15th century toward the early 16th century and were some of the most popular European medieval swords due to their versatile effectiveness in battle. As said by Oakeshott, the Type XVIII and its sub-types were “the most widely used swords between c. 1410 and 1510 all over Europe”.

Type XVIII’s blade design can be traced back to the blades of the Roman era and Bronze Age swords. Its fashion temporarily went out of use in favor of more cut-oriented blades such as the Migration or Viking Swords, but tapering blades with pointy tips made a comeback in the 14th century, which would also be frequent on a type XVIII.

Oakeshott explains that the return of the XVIII was due to its excellence in cutting and the metallurgical developments that enhanced its thrust against certain types of armor.

Oakeshott, as well as other sword typologists, have a problem classifying type XVIII swords. As a result, multiple sub-types have emerged because their blade designs are effective for cut and thrust actions. Oakeshott changed his typology regarding the XVIII parent and its sub-types. Still, the sword was so favored that bladesmiths tried to emulate it’s different versions.

The Oakeshott type XVIII sword was immensely popular during its era and remains one of the most revered and studied blades to this day. It is one of the most replicated swords with magnificent quality, making it a staple among European sword enthusiasts and training academies.