Guide Into The Legendary Masamune Swords

What’s in this article?

In the long and exciting history of swordmaking, blades brandished by the Samurai warriors of feudal Japan are known to be some of the most formidable, yet beautiful weapons ever made. Reasons for this include their intrinsically artistic creation, deathly engineering, and the quality of steel they were forged with.

Japanese swords and knives such as the Tachi, Katana, Wakizashi and Tanto are famous in Samurai culture. Out of all of these swords ever made, the ones designed and created by the legendary swordsmith Goro Nyudo Masamune are the most revered.

Masamune not only made some of the most heralded Samurai swords, but also tutored some of the great swordsmiths that followed him, meaning he left a legendary legacy. In this article we will learn the history behind the

Goro Nyudo Masamune

(A Woodblock Print by Hiroshige, depicting Masamune at work)

Before we look in detail at the blades made by the hands of the Japanese swordsmith master, we need to know a bit more about him.

Goro Nyudo Masamune or simply ‘Masamune’, is the name of one of the world’s greatest swordsmiths. Born circa 1260 AD, Masamune’s life and death dates are not certain, like many other parts of his career and his contemporaries. He came from a coastal region south of modern day Tokyo, known as the Kanagawa Prefecture and was active in the Kamakura period of Feudal Japan.

Masamune is believed to have studied the art of swordsmithing under the guidance of Shintogo Kunimitsu (whose life dates are also unknown, but believed to also be from the 13th to 14th centuries).

Kunimitsu is regarded as a master swordsmith himself and thought to be the original developer of the Soshu Style of Japanese swords. Goro Nyudo Masamune is famed to have taken the Soshu style to its height of excellence.

Feudal Japan and the Samurai Class

A quick look into Japanese history will further our understanding of the importance of the Samurai swords Masamune produced.

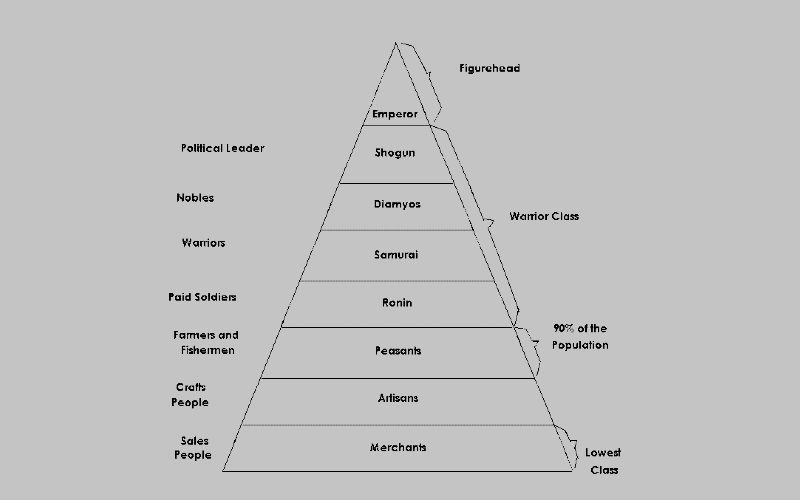

Under the governance of Feudal Japan, Kanagawa became the seat of power in the Kamakura period. This was a time where the ruling class was known as the Shogun; families of military leaders that held more authority over the Japanese civilians than the Emperor.

These Shoguns worked closely with the daimyo (rich and powerful landowners), who in turn enlisted the services of the Samurai, the warrior class, who would protect and fight on their behalf. This guardianship was taken so seriously that in the instance of defeat, it was perceived as dishonor and Samurais would commit the infamous suicide ceremony known as Seppuku. Therefore, a Samurai swordsman had to carry the best weapons available.

The Soshu Style

The Soshu style of

The Soshu style is understood to have originated at the hand of Shintogo Kunimitsu in the Kanagawa prefecture. It was developed under the influence of other great swordsmiths who had moved to the region from the Yamashiro and Bizen areas.

Another factor that led to the development of this greater caliber of swords were Mongol invasions in the late 13th century. Their blood thirsty invasions along with other threats from rebellious clans reinforced the need for even more effective Samurai weapons.

A Glossary of Technical Terms

In order to understand the Soshu style, specifically the masterly creations of Masamune, here is a simplified glossary of terms that make up a legendary Masamune

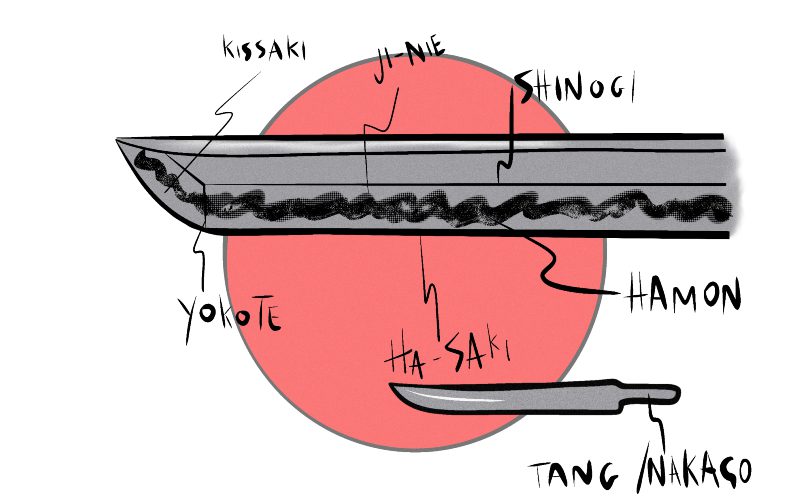

- Kissaki: The tip of the blade, starting from the yokote and covering the surface area of the blade.

- Yokote: The visible line dividing the kissaki and the main body of the blade.

- Nagako or Tang: The tang refers to the metal that runs from the end of the blade and inside the hilt. The length of which indicates if a

sword is “full tang” or not.

- Hamon: The pattern on the cutting edge, formed by the crystalline structure as a result of the high temperatures of the hardening process.

- Ha-Saki: The cutting edge of the blade.

- Shinogi: The raised ridgeline that runs the length of the blade from the yokote to the nagako.

- Ji: The surface area between the shinogi and the hamon.

- Nie: Small, individually visible martensite crystals that make the hamon.

- Nioi: Like nie, but not individually identifiable, often appearing wavy in the hamon.

- Ji-Nie: A large amount of nie which appears across the ji.

- Tetsû: The material the

sword is made of, directly translated in Japanese tetsu is iron but here it is understood as steel.

The Soshu style can be recognised based on the thinner sword blades. Made from tetsu that is stronger and tighter, it also has a large wood grain effect that would run from the kissaki to the nagako along the Ha-Saki. Typically the hamon would have a sort of patterned effect either from nie or nioi.

How Masamune made the style his own

Despite achieving immense strength and power, the extreme heat needed to create such a high carbon steel meant the blade would be prone to brittleness and could potentially break in battle. Masamune managed to overcome this difficulty by blending a harder and softer steel together, adding an incredibly important element of durability.

This duplex of steel led to one of the signature elements of a Masamune blade, a beautiful and unique pattern of ji-nie on the hamon of the blade. It has been said that the pattern is reminiscent of ocean waves when the blade is on its side.

He further developed the Soshu style by shortening the blade length and added his own spin onto both longswords and shorter swords such as his famous Tanto trio.

Of course Masamune would sign his creations by leaving an inscription on the mei. However, one reason for the lack of these iconic blades is partially due to the powerful family who has employed Masamune to manufacture his swords. The all powerful Tokugawa family enlisted the skills of the great swordsmith to produce his magnificent weapons for their best Samurai warriors.

As a contracted employee of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Masamune is believed to have left out his personal inscription on these blades, potentially making many Masamune swords unidentifiable. This has led historians to suggest that there could be any number of the iconic blades amongst the collections of Samurai swords out there.

Adding to your Personal Collection

Sadly, it almost goes without saying how highly unlikely it is that an enthusiast would ever be able to add a real Masamune blade to their collection. However, bearing in mind the style that Masamune made his own, you might be able to find a replica that meets specifications.

When looking for a Katana or a Wakizashi etcetera in the Masamune style, some of the characteristics to look for are:

- Extreme amounts of Ji-Nie – Remember swordsmithing in Feudal Japan where it is a complex process which forges powerful swords, extreme ji-nie is beautiful and synonymous with a Masamune

sword .

- Tightly forged steel – Tight tetsu is representative of works by Masamune and Soshu swords in general. Settle for nothing less than the most durable, powerful, and swift swords.

- A true artistic quality – Expanding on No. 1, a blade made in the Masamune style must have an intrinsically artistic quality which balances its lethal power. Not only must there be ji-nie, but the

sword must appear balanced, polished and a work of art.

Authentic Masamune Sword Blades

Now that we understand their origins, we can look at some of the iconic blades Masamune actually crafted, some of which are on display today.

Honjo-Masamune

The Honjo-Masamune

The Honjo-Masamune takes its name from its handler, General Honjo Shigenaga. After it served its lethal purpose, it eventually came into the possession of the renowned Tokugawa Shogunate family and became the emblem of their power.

However, tragedy struck after World War II when the USA outraged Japanese nobility by demanding they hand over all of their handheld weapons. To lead by example, Tokugawa Ieyasu handed over the Honjo-Masamune.

From that point on, the world’s greatest

Shimazu-Masamune

Another

Although it doesn’t entirely make up for the loss of the legendary Honjo-Masamune, experts confirmed the authenticity of the finally recovered Shimazu-Masamune in 2014. It is now displayed at the Kyoto National Museum after being donated by a rare

Ikeda-Masamune

The Ikeda Masamune is a Katana

A Katana made by Masamune would be expected to cut through armor, withstand offensive strikes and make swift and deadly blows in one fell swoop. Currently, the Ikeda-Masamune is held in the Tokugawa Art Museum and labeled as “important cultural property”.

Hocho-Masamune

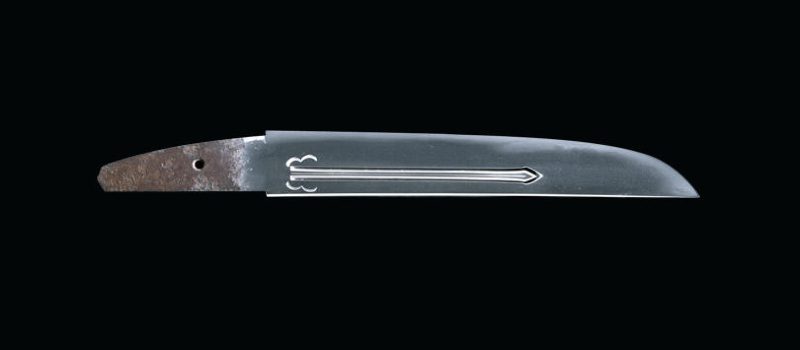

The Hocho-Masamune is a Tanto blade and is classed as a Japanese national treasure. The word “Hocho” translates to “kitchen knife”, a term used to describe the Hocho Masamune as it has a significantly thicker blade, like a kitchen knife, than the blades of a traditional Tanto.

Whilst it is likely that Masamune forged many Tanto swords throughout his career, this Hocho-Masamune, which is held in the Tokugawa Art Museum, is the only known example of a Hocho style Tanto made by Goro Nyudo Masamune left. There was once a trio of these Hocho blades but two have sadly been lost, giving this last remaining one immense value.

The Hocho-Masamune is 23.9cm long and was originally owned by Tokugawa Leyasu. Since the original trio was so unique and desirable, the tragedy of the Hocho-Masamune being the only Hocho blade left only enhances the greatness and mythicality of Masamune’s legacy.

Fudo-Masamune

This blade is also a Masamune Tanto but it is made in the style of a traditional Tanto design, unlike the three Hocho style Tantos that hold the greatest fame. You can immediately see the differences between the Fudo-Masamune and the Hocho-Masamune.

The Fudo is 24.8cm long with a much thinner blade, typical of a traditional Tanto. Despite it not being a Hocho style Masamune, any Tanto blade created by the master is a significant piece. The Tanto would be carried into battle by a Samurai, acting as a backup blade.

Sincere defeat is considered a great dishonor, the tanto was a weapon used to carry out the suicide ceremony known as seppuku. Also held in the Tokugawa Art Museum, the inscription on the tang simply reads “Masamune”.

Ichian-Masamune

The final Tanto blade is also held in the Tokugawa Art Museum, but in this case is only attributed to Masamune. This means that it isn’t signed but its style and characteristics make it highly likely that Masamune was the creator.

It is 24.5cm long and holds no inscription. Instead it is the style and wave-like hamon which indicates it was crafted by the ultimate swordsmith.

Unfortunately, over the 700 years since Masamune created his masterpieces, many of the swords have been lost, stolen, or perhaps mistaken as the creation of another Swordsmith due to the lack of inscriptions.

Who was Muramasa?

Muramasa is another Japanese swordsmith, whose name often follows Masamune due to the uncertainty regarding when Muramasa was alive. Legend has it that Maramasa personally challenged Masamune to a duel in order to determine who was truly the greater swordsmith.

Both aspects of this myth have been rebuked. Whilst historians have suggested that the two were almost definitely not alive at the same time,

Muramasa was known to have been ill-tempered and erratic, causing his swords to hold an aura of darkness. Where Masamune’s weapons are seen as a force for good and an emblem of the Samurai, Muramasa’s blades are said to act on behalf of evil.

Despite this Muramasa is still renowned as a master swordsmith, in his own troubled way.

Conclusion

The swords crafted by the hand of Goro Nyudo Masamune of Kamakura were of such a high quality and so greatly sought after that they earned him the legacy of being one of the greatest swordsmiths to have ever lived. He even came to be known as one of the tenka sansaku or “three masters under heaven”, alongside his contemporaries Yoshimitsu of Kyoto and Yoshihiro of Etchū.

To see a real Masamune