Jihada: The Grain Pattern of the Blade

What’s in this article?

Often appearing as intricate and fascinating patterns, the jihada is an attribute of a traditionally forged Japanese blade. It is the grain pattern within the steel that results from repeated folding during forging. Its appearance varies from sword to sword, depending on how the swordsmith worked the steel.

Let’s explore the unique characteristics of the jihada, its various types and patterns, how it is formed, and why it is significant in sword appraisal.

Characteristics of the Jihada

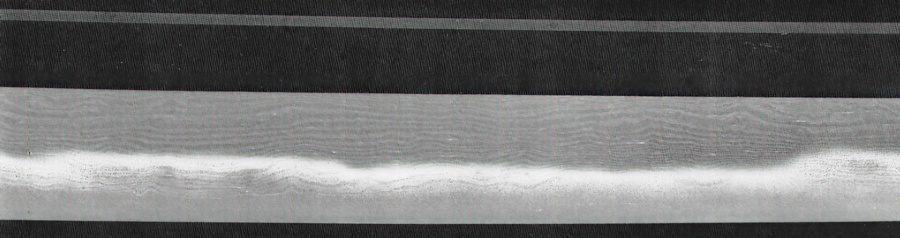

The jihada can vary greatly due to differences in the forging techniques of different swordsmiths. However, a sword blade must have a good polish for the grain patterns to be visible.

Here are the unique characteristics of the jihada and a few terminologies used to describe its appearance:

Structure and Composition

In traditional Japanese swordmaking, swordsmiths repeatedly fold the steel to refine it. The forge-folding results in an intricate surface pattern in the steel, the jihada. Depending on how a swordsmith folds and hammer the steel, one or several patterns may be visible. The appearance of the grain patterns is also influenced by the amount of impurities, carbon content, and so on.

For example, the billet’s surface exposed to direct hammering develops a wood-grain-like pattern. On the other hand, the sides of the billet will have a straight grain pattern. After the forging process, a swordsmith can use either the hammered surface or the layered sides of the billet to form the blade.

Appearance of the Grain Pattern

A jihada can be very clear or nearly invisible. Generally, the more uniform it is, the better the skill of the swordsmith. While a grain pattern might be mixed with areas of different forging structures, these areas should not stand out unnaturally. However, some appearances can also be a characteristic feature of an individual smith or sword making school.

The appearance of a jihada may be described as fine (komakai) or dense (tsunda). Seibi also refers to a very fine and beautiful hada. The opposite of a fine hada is rough (arai) or standing-out (tatsu), in which their individual layers are clearly visible. However, a rough hada is an unnaturally rough grain pattern, while a standing-out hada suggests that the swordsmith intended it.

Size of the Grain Pattern

A jihada can be classified according to size, using the prefixes ko- (small), chu- (medium), and o- (large). For example, a grain pattern with many circular motifs is called mokume hada, and it can be classified as ko-mokume (small), chu-mokume (medium), or o-mokume (large).

Types of Grain Patterns

Japanese swords usually feature one pattern or combination of patterns on a single blade. Different grain patterns are associated with different smiths and schools of various historical periods.

1. Masame Hada (Straight Grain)

The masame hada (柾目肌) is a straight grain pattern that runs parallel to the cutting edge. There are various kinds of masame grains: the pure masame, the running masame (a straight grain pattern tending itame grain), and the partial masame that is only visible in one section of the blade.

The masame hada is mainly associated with the Yamato tradition of sword forging. An obvious masame hada is a characteristic of blades of the Hosho school. It can also be seen in blades made by the Shinto smiths of the Sendai Kunikane lineage.

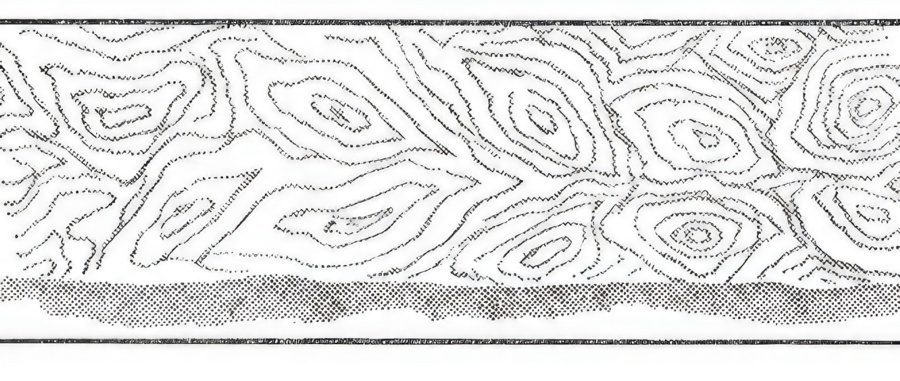

2. Mokume Hada (Burl Grain)

The mokume hada (木目肌) features obvious burls, irregular concentric circles, and swirls, similar to the burl grain seen in the wood. The term moku literally means tree or wood, and me means pattern. The visible burls are often called uzumaki (渦巻), meaning whirlpool. Sometimes, these burls are called jorin (如輪) or nenrin (年輪), both mean annual tree rings.

The mokume hada was popular throughout all regions and periods. It is mainly associated with the Bizen tradition. Its most prominent examples can be seen in the blades of the Oei-Bizen school during the Oei era, from 1394 to 1428. The most famous swordsmiths of this period were Moromitsu, Morimitsu, and Yasumitsu.

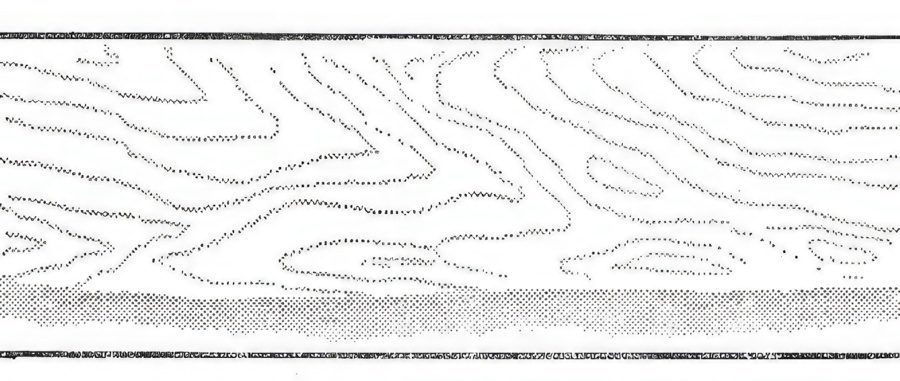

3. Itame Hada (Wood Grain)

The itame hada (板目肌) resembles a wood grain or plank pattern. A mix of concentric circles and wavy parallel lines can be seen when cutting a log into planks. It looks like a combination of masame hada and mokume hada. However, it does not have running lines like masame and is not burl like mokume.

More often, a grain pattern is itame unless obvious burls (mokume) are present. If a few burls are noticeable, it is likely an itame mixed with mokume. The itame hada is the most common grain pattern on Japanese swords. It is often associated with the Soshu tradition, typically seen on Masamune, Hiromitsu, and Sadamune blades.

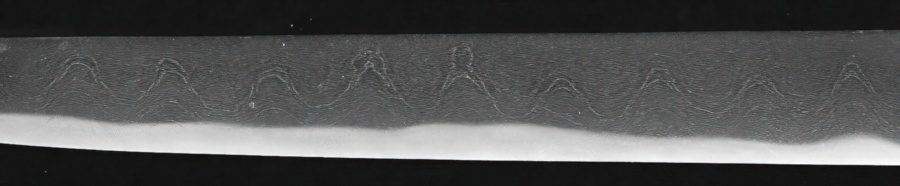

4. Ayasugi Hada (Undulating Wave Grain)

The ayasugi hada (綾杉肌) features curvy lines or large waves. It was named after the wavy carving pattern inside the Japanese lute samisen. The ayasugi hada was the trademark of the Gassan school, hence also called Gassan hada (月山肌). It can also be seen on the blades of Satsuma Naminohira school. Later, the Gassan smiths of the Shinshinto and Gendaito eras revived it.

5. Nashiji Hada (Very Fine Grain)

The nashiji hada (梨子地肌) features very fine grain and is difficult to see. It can be seen on the blades of early Yamashiro schools, such as Awataguchi and Sanjo. Some Osaka Shinto swords also feature the nashiji, especially the works of swordsmiths Tsuda Sukehiro, Ikkanshi Tadatsuna, and Ozaki Suketaka.

6. Konuka Hada (Rice Grain)

The konuka hada (粉糠肌) resembles rice bran (konuka) hence the name. Its patterns are generally fine and uniform. It is believed that the Hizen swordsmiths tried to emulate the nashiji hada of Yamashiro, resulting in the konuka hada. Hence, the grain pattern is also called Hizen-hada (肥前肌). Generally, the name konuka hada is only applied to Hizen blades.

Facts About the Jihada

The Japanese term jihada (地肌) refers to the visible pattern of the forging structure of the steel. The term hada (膚) literally means skin, texture, or grain and is often used to refer to the jihada of a blade.

Sword steels are not folded thousands of times.

The process of refining and folding of the Japanese sword is called tanren. Contrary to popular belief, the jacket steel of a blade is only folded ten to fifteen times. The forge-folding results in multiple layers being doubled with each fold. Therefore, the jihada results from about 1,000 to 30,000 layers—not folds.

A polisher brings out the jihada and other artistic features of a blade.

Apart from making a sharp cutting edge, a polisher also refines the artistic features of a Japanese blade, such as the jigane (steel surface), jihada (grain pattern), and hamon (temperline pattern). Generally, a fine hada is essential to the finished polish. Also, the polisher has to know when to stop refining the hada, or it will become too obvious.

An indiscernible jihada was often referred to as muji hada.

Many shinshinto and gendaito blades have too small grain patterns, and their steel is too tight in texture, making the jihada difficult to identify. These were often referred to as muji hada. However, those seemingly grainless blades formerly described as muji can now be brought out with polishing due to the improved techniques.

A blade may also feature additional patterns and shapes called hataraki.

The hataraki refers to the activities within the blade’s body and the hamon (temperline pattern). These activities appear as additional patterns and shapes in the blade and are crucial when identifying its smith or school. Among them is the ji-nie, the formations of the nie or large martensite crystals, in the blade’s body. There are also black lines called chikei, appearing along the pattern of the jihada.

Each school of the Gokaden had its characteristic jihada.

The Gokaden refers to the five major sword making traditions by the end of the Kamakura period and during the Nanbokucho period. It consists of the Yamato, Yamashiro, Soshu, Bizen, and Mino schools. Each gave its swords their characteristic grain pattern, hamon, blade shape, and other details.

Some showa-to swords featured grain patterns on their blades.

Blades made from non-traditional steel are called showa-to, distinguishing them from traditional blades made from tamahagane. The showa-to widely ranged in quality and features, with the most expensive blades featuring a jihada and hamon (temperline pattern). However, the least expensive ones lacked these artistic features, so many collectors regard them as incomplete or not properly-made.

Some old blades that don’t show grain patterns may have tired blades.

Over-polishing, poor restoration, and repairs can ruin the details on the blade surface. Too much polishing can remove the hard, high-carbon steel jacket (kawagane) that forms the blade’s surface, exposing the core steel (shingane). Swords in this condition are referred to as being tired. These blades have areas that don’t show visible forging structures.

Other types of Japanese blades also have a jihada.

The jihada is a characteristic feature of sword blades, from tachi to katana and wakizashi. Still, it can be seen in tanto daggers and spearheads. Some Japanese yari had blades featuring a straight grain pattern (masame hada). These also feature a hamon (temperline pattern), often a suguha (straight temperline pattern). However, many have tightly forged blades and barely show their surface patterns.

Conclusion

The jihada is a notable feature of an authentic Japanese-folded steel blade and a crucial part of Japanese sword appraisal. It is the visible surface pattern of the steel and can help determine the blade’s swordsmith, school, and period. Some blades only have one type of hada, but more often, a blade features mixed types of grain patterns.