Samurai Swords: Types, History, and Development

What’s in this article?

Most recognized for their curved blades, the samurai swords were among the finest weapons in history. Early swordsmiths perfected the art of swordmaking and adapted their swords to changing military strategies of the time. These blades became the symbol of the samurai’s elevated status in Japanese society and are now works of art.

Let’s talk about the different swords the samurai used, their history, development, and why collectors consider them to be among the finest blades ever made.

Different Types of Samurai Swords

Battles and military strategies dictated the changes in

1. Katana

The most popular Japanese

2. Wakizashi

The shorter version of the Japanese katana, the wakizashi, was the samurai’s constant companion. It measures around 45 centimeters long and features the decorative mountings of the long

3. Daisho

The term daisho translates as large and small, apparent in the Japanese words daito (long

4. Tachi

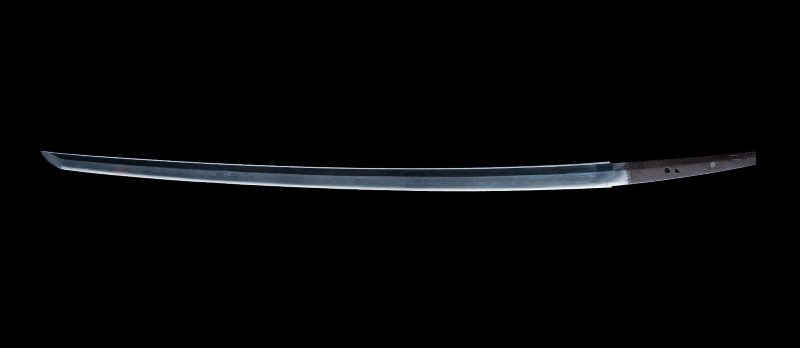

The first Japanese

For most of Japanese history, it was the proper

5. Tanto

The tanto was the ceremonial dagger of the samurai, used in seppuku ritual suicide to avoid capture after battlefield defeats. It first emerged as a practical weapon but eventually evolved into a decorative blade with all the fittings of a samurai

The tanto refers to Japanese blades with a length of less than 30 centimeters, so it is considered a dagger. In earlier times, the sunnobi tanto had longer than usual blades, blurring the line between a long dagger and a short

6. Odachi

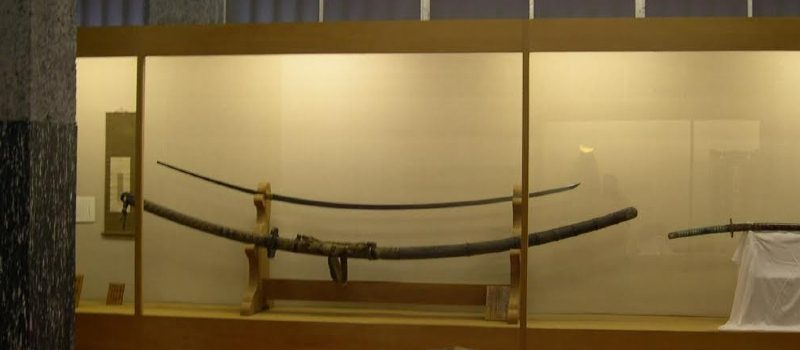

The longest samurai

However, the samurai mostly used them during the Nanbokucho period from 1336 to 1392 as these extremely long swords were difficult to wield. During the Ōnin War period, some odachi reached about 220 centimeters long. Some enormously long examples still exist in temples and shrines, but those only served as offerings—not battlefield weapons.

7. Nagamaki

A samurai

It became known as the nakamaki nodachi, meaning a nodachi wrapped around its middle, which we know today as nagamaki. It usually had a blade length of 90 centimeters or a handle of 120 centimeters. The warriors used it as a

Characteristics of Samurai Swords

Japanese swordsmiths have perfected the art of swordmaking, making the

Type of Steel

Japanese swordsmiths work with a traditional form of steel called tamahagane, produced in a tatara smelter in Japan. The tamahagane is one of the best steel for swords, though other swordsmiths use sponge iron or electrolytic iron, which are relatively cheaper.

Many compare Japanese blades to the so-called damascus blades, which appear to be a combination of low carbon steel and high carbon steel, resulting in the ornate damask pattern. However, the Japanese steel is more refined, making the samurai

Blade Construction

Hardened steel could hold a sharp edge, but it is unsuitable for the body of the blade because it is too brittle. So, the Japanese swordsmiths use softer steel for the core and hard steel for the outer surface of the blade. Samurai blades are also clay tempered, hardening only the cutting edge by covering the blade in clay.

Blade Appearance

The samurai swords are most known for their curvature and sharp edges. The hamon shows that the swordsmith hardened the steel, while other attractive features of the metal, such as color and grain pattern, reveal the skill of a smith.

Blade Shape and Curvature

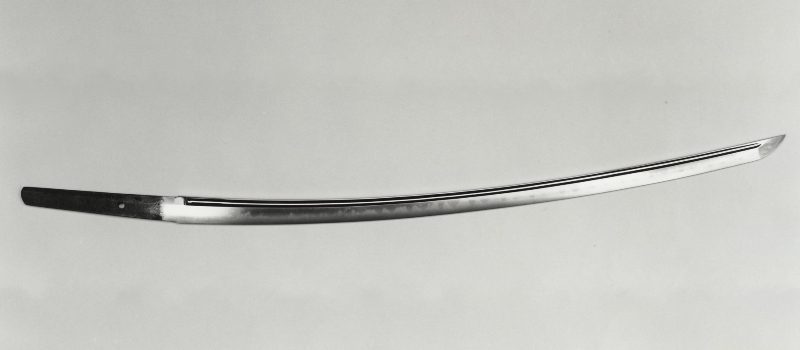

Samurai blades are slightly curved and single-edged. However, the overall shape or sugata of old blades will also reflect the period they came from. Generally, the more strongly curved

Hence, the tachi

Decorative Grooves or Hi

The groove or fuller lightens the blade or strengthens it by making it stiffer. Sometimes, it also serves as a decoration. Some designs are straight groves to the end of the tang, while others are twin grooves or a mix of straight and curved.

Decorative Carvings or Horimono

Horimono are often traditional designs, such as dragons, deities, Buddhist motifs, Sanskrit characters, bamboo,

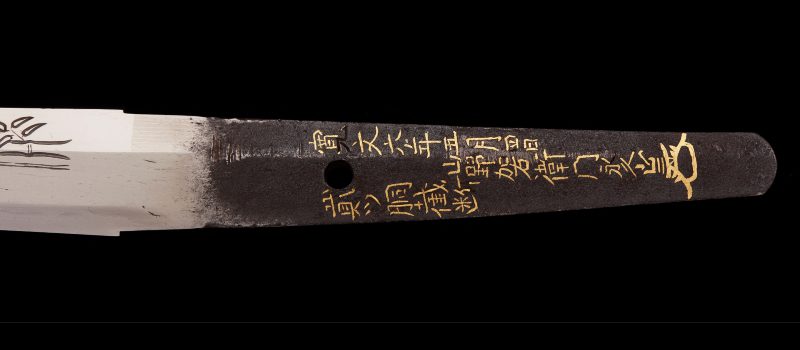

Tang and the Signature

Some samurai swords are signed, especially ones that meet the standards of the swordsmith. Today, contemporary swordsmiths often chisel their mei or signature on the tang. However,

Aesthetic Features of the Blade

The characteristic feature of the samurai

Temperline Pattern or Hamon

The hamon, or temperline pattern, serves an aesthetic purpose but also shows the cutting power of the blade. The cutting edge is hardened steel, which is also brittle and chips easily. Generally, older Japanese swords have a straight and very narrow hamon, which chips easily across the broad portion of the cutting edge.

On the other hand, Heian-period and later blades have wider hamon, especially the gunome type resembling a row of teeth, which prevents a chip from spreading laterally. Some patterns include a series of clouds, arcs, zigzags, waves, and so on. As a rule of thumb, a good hamon has a well-defined shape over its entire length.

Steel’s Appearance or Jigane

Unlike factory-produced steel, Japanese steel is usually darker in color. The particular forging and hardening methods typically alter the actual hue of the steel. Generally, Koto or old blades are dark gray, while Shinto and Shinshinto blades tend to be lighter.

Sword collectors often describe the high-quality Kamakura period blades as having a fine dark gray velvet color. The hamon is often whitened or polished to stand out from the darker surface seen on the rest of the blade.

Grain Pattern or Jihada

The jihada or grain pattern shows that the samurai

Size and Length

The samurai swords generally have the same blade construction but are classified according to length. In the Japanese unit of length, 1 shaku is equal to 30.3 centimeters. The blade length starts from the munemachi at the base of the blade to the tip. Japanese swords of more than 2 shaku or over 60 centimeters long, are considered daito or long swords.

On the other hand, blades shorter than 2 shaku yet longer than 1 shaku are considered shoto or short swords. Therefore, the samurai katana

Sword Mounting

The samurai often reset their blades in decorative mountings according to their taste and occasion. Today, Japanese tsuba or sword guards are collector’s items in their own right.

Hilt or Tsuka

Samurai swords often had wooden handles, usually magnolia wood covered with ray skin. The hilt also features matching fuchi and kashira. The former is near the hand guard and the latter on the pommel. Decorative mountings sometimes feature a menuki placed under the handle wrapping.

Sword Guard or Tsuba

The tsuba protected the samurai hands, but it eventually became a work of art as artisans crafted ornamental designs. Most handguards are disk-shaped, but others have a rectangular shape or four-lobed design called mokko. Some also feature elaborate cut-out designs and high-relief carvings.

Tsuba artisans also incorporated precious metals and colored stones. During the Edo period, the samurai preferred elaborate tsuba designs rather than functional ones, mostly themes of nature, mythology, legend, religion, and traditional Japanese motifs.

Scabbard or Saya

Unlike Western swords where scabbards tightly fit on the blade, the Japanese saya holds the

The Japanese

Facts About the Samurai Swords

Samurai swords were not only deadly weapons but also the symbol of the warriors’ elevated status in Japanese society and family heirlooms.

Here are the things you need to know about the samurai swords:

The technology that led to the development of samurai swords likely originated in China.

At first, the Japanese imported swords from China. Tang dynasty

The samurai swords were only later weapons of combat.

We often associate the samurai mainly with swords, but their principal weapon was the bow-and-arrow. The art of Japanese

The tachi functioned as a cavalry

The two long swords can be easily distinguished by how the samurai wore them. The tachi functioned better as a cavalry

The daisho, a sword set of long and short swords, was exclusive to the samurai class.

The samurai had to be armed and prepared during hostile times, so they wore the daisho, consisting of katana and wakizashi, in civilian dress. Before entering public buildings, a warrior traditionally left his katana at the entrance, so the wakizashi served as a backup

The samurai carried several swords with them.

The katana and wakizashi are the most famous samurai swords, but they also carried the tanto dagger on their belt. In a well-known depiction of Honda Tadakatsu, he wore two companion swords, the tanto and the wakizashi.

The samurai flaunted their personality and wealth on luxurious

Japanese blades were removable from the

Not all tanto mountings included a tsuba or hand guard.

The tanto often had the traditional mounting of the samurai

The samurai swords served as ceremonial weapons.

To avoid capture after battlefield defeats, the samurai performed seppuku, often called hara-kiri in the West, to achieve an honorable death. They initially used the short

Japanese martial arts utilize training swords like bokken and iaito.

In iaido, practitioners use a blunt katana or iaito for the saya practice, but not in contact drills. The Japanese katana is also the highlight of kenjutsu, but practitioners train with a wooden

History of the Samurai Swords

The long history of samurai swords can be classified into Japanese

Koto Era

Japanese swords that came during the mid-Heian period through the end of the Momoyama period are considered koto or old swords. The Koto era is also known as the Old

In the Heian Period (794 – 1185)

During the mid-Heian period, the Japanese swordsmiths had improved steelworking techniques, so the swords also developed curvature. The Heian warriors using these blades fought from horseback, and a curved blade was more efficient in slashing than a straight one. Swords of this period are called tachi, worn slung from the waist with the edge facing down.

In the Kamakura Period (1192 – 1333)

From 1192 to 1333, feudalism was firmly established in Japan. The samurai class had a strong demand for swords, which led to the production of better, more functional swords. Some of the main events of the Kamakura period were the Mongol invasions, between 1274 and 1281, which strongly influenced

Sword designs included the addition of a soft steel core and more complex hamon, which made samurai swords more efficient. Swordsmiths also began carving grooves and horimono talismans to imbue protective qualities to the blades. The tachi blades also became wider, thicker, and heavier, requiring two hands to use. Many smiths also produced tanto daggers for close-quarters combat.

In the Nanbokucho Period (1331 – 1392)

During this period, five major

In the Muromachi Period (1338 – 1573)

It was customary to carry swords in the tachi style, slung from the belt with the edge facing down. Towards the beginning of the Muromachi period, a few low-rank samurai habitually wore their swords edge up into their belts. Eventually, it became a trend adopted by high-rank samurai.

Within the period emerged the Sengoku period, a time of constant civil war in Japan. There was a huge demand for swords, which resulted in mass-produced blades of lower quality. The uchigatana emerged for fighting indoors, as it could be wielded with one hand and was much lighter than the tachi.

The wearing of the uchigatana edge-up allowed drawing and slashing actions in one stroke, contrary to the two motions needed when the samurai carried the tachi edge-down. Also, the mounting hardware of the tachi was too bulky for daily use, especially when not wearing armor.

In the Momoyama Period (1574 – 1600)

In 1588, chief military commander Toyotomi Hideyoshi confiscated swords from all non-samurai. During this period,

Shinto Era

Samurai swords produced around 1600 are considered shinto or new swords. During the New

In the Edo Period (1603 – 1867)

During the early part of the Edo period, the daimyos of Japanese provinces needed swords to equip their samurai. So, several swordsmiths flocked to major cities such as Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka, marking the beginning of the Shinto or New

By the beginning of the period, wearing daisho, a

Shin-shinto Era

The Shin-shinto or New, New

In the late Edo Period

In the late 1700s, swordsmith Suishinshi Masahide revived the interest in old Japanese swords, particularly the Koto blades from the Kamakura and the Gokaden techniques. He trained several swordsmiths to craft blades as functional as the Koto swords, marking the beginning of the Shin-shinto era.

The samurai swords of the Shin-shinto era were modeled on old blades, but they acquired character and style of their own. Swordsmiths used several forging methods and experimented with new

Gendaito Era

Generally, Japanese swords made from the Meiji Restoration until the present are considered modern swords or gendaito.

In the Meiji Period (1868 – 1912)

The Meiji Restoration ended the Tokugawa shogunate and restored imperial rule. In 1876, the Meiji government abolished the samurai class and banned wearing swords in public. During this time, traditional Japanese swords served as art objects rather than functional weapons.

In Modern Period (1912–Present)

In the early 1930s, many blades were mass-produced for officers in the imperial army. They had the traditional shape of samurai swords, but none of the aesthetic features of a hand-forged blade such as the hamon and grain pattern. Also, these army swords were made from foundry steel—not the traditionally smelted tamahagane.

Japanese swordsmiths managed to preserve the traditional methods of swordmaking. The recently produced swords are often referred to as shinsakuto, to differentiate them from the other gendaito. Most swordsmiths craft Bizen-style blades, which are in-demand to collectors. Others also experiment with the overall

Samurai Swords in Pop Culture

The Japanese

Today, Miyamoto Musashi is likely the most popular samurai. In Japanese folktale and legend, he was undefeated in at least 60 duels and even beat his rival Sasaki Kojiro with his wooden

The katana

Are Samurai Swords Illegal in Japan?

The Japanese government allows ownership of samurai swords for home use, and these blades must come with certification and permit. The rule only applies to antique swords and newly made swords, as training swords like iaito are exempted. Also, the government does not register army swords and requires them to be destroyed.

In order to maintain the quality of Japanese swords, licensed swordsmiths can only produce a maximum of two long swords like katana or three shorter blades like wakizashi and tanto per month. However, the only legal weapons to carry outside your home are blades shorter than 6 centimeters, which means you cannot bring around your tanto dagger as a self-defense weapon.

Maintenance and Cleaning of Samurai Swords

Regardless of the value of the blade, collectors must treat the

Here are the things you need to know about the maintenance of samurai swords:

Use products and tools that reflect the quality of your

Traditional cleaning tools for samurai swords include the nugui gami Japanese paper for removing oil and dirt, uchiko powder ball for cleaning the blade, and choji or clove oil for preventing rust. Using high-quality cleaning products is recommended, as poor quality uchiko, for instance, could damage the polish of the blade.

Martial art practitioners can use inexpensive cleaning products for iaito swords.

Martial arts practitioners can utilize inexpensive products for practice swords like iaito. Some opt for facial tissues or soft pieces of paper to remove oil and dirt, as long as it does not contain aloe and perfumes. Instead of choji or clove oil, many use scented oil or oil cloth to prevent rust.

Samurai swords require cleaning every six months.

It is best to prevent rust rather than to have to remove it.

The tang is never cleaned or polished.

Over time, the rust builds up on the tang, but it is actually an indicator of the

Take the samurai

Do not use any abrasive materials or chemicals when cleaning the

An experienced polisher can mend some subtle flaws in samurai blades.

Several types of flaws or kizu diminish the beauty of the blade. A polisher may be able to reshape a broken kissaki or point as long as the break does not extend past the tempered point or boshi. Unfortunately, if the hamon is interrupted by a crack or chip at any part of the blade, it is considered a fatal flaw.

Avoid cutting hard objects that will damage the blade.

Practitioners utilize battle-ready swords for tameshigiri, cutting bamboo, tatami mats, water-filled bottles, and fruits. However, hard objects like tree branches, weeds, and scrubs will likely damage the blade, usually beyond repair.

Conclusion

Japanese swordsmiths of the past took great pride in their craft and produced some of the finest blades in history. The worth of Japanese samurai swords is more than their material value. Apart from being art objects, they represent the history and legacy of their past owners.