Ricasso: The Unsharpened Section of the Blade

What’s in this article?

Commonly seen on European swords and daggers, the ricasso is the unsharpened part of the blade near the hilt. It allows the execution of specialized grips and various techniques to enhance the control and maneuverability of the weapon. It may have appeared during the mid-14th century or even earlier, but only became a typical feature on swords and daggers in the 16th century.

Let’s explore the appearance and function of a ricasso, how it varies in different types of blades, and how it provides additional leverage in combat.

Design and Appearance

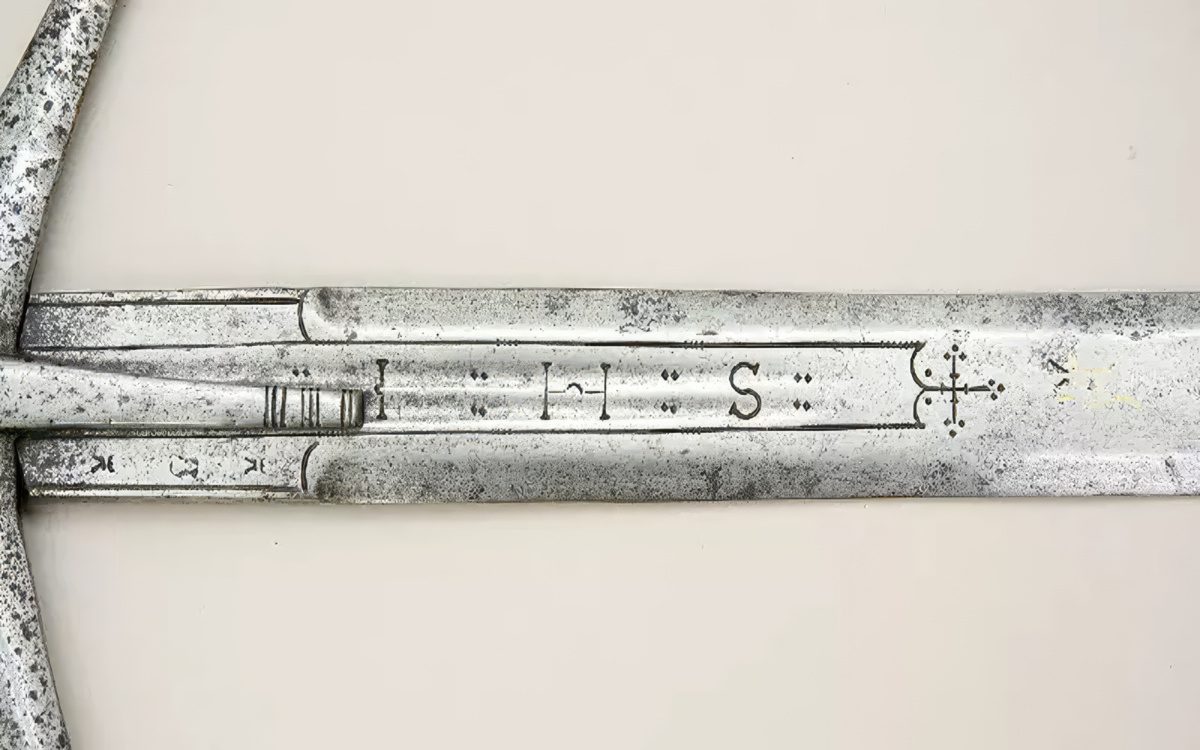

The ricasso is the thickest part of the blade and unsharpened, unlike the cutting edge. It usually bears the maker’s mark and may feature fullers or grooves. In Scottish claymores, the ricasso is held by the langets—or metal strips extending from the crossguard. On the other hand, the ricasso of the German zweihander or great sword, often has a leather wrapping for an easier grip.

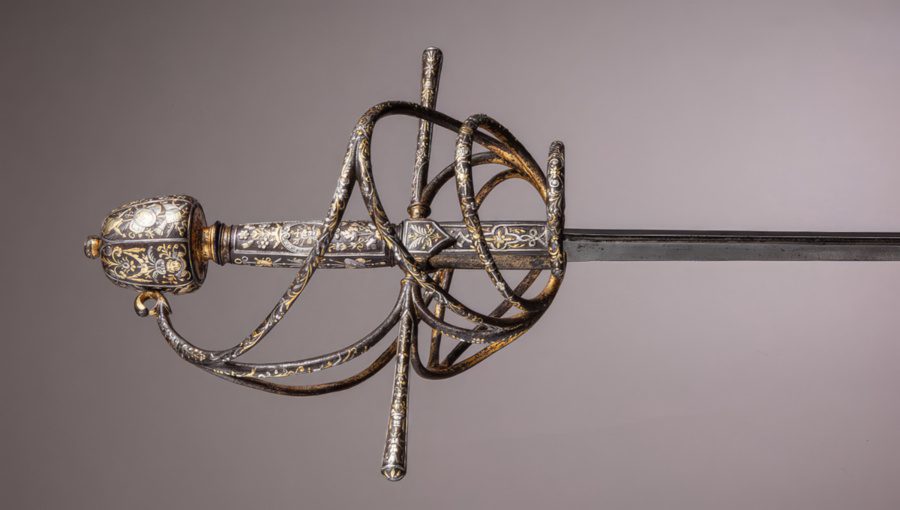

Rapiers have a triangular or hexagonal blade cross-section, so their ricasso appears more squared off. They often feature protective rings over the ricasso. In a swept-hilt rapier, side rings and finger guards, sometimes called arms of the hilt or branches, protect the fingers gripping the ricasso.

However, many replica swords only have decorative finger guards or arms, which do not have enough room for the finger. On the other hand, cup-hilted rapiers have ricasso that is enclosed by their cup guards.

Length and Width

The length and width of a ricasso vary from sword to sword. For instance, a sword with a blade length of 37.5 inches (95.2 centimeters) may have a ricasso of about 3 inches (7.6 centimeters) long and 2.85 inches (7.2 centimeters) wide. However, the measurement of a ricasso may be shorter, longer, narrower, or broader, depending on the sword, blade type, and intended use.

Function

The ricasso at the base of the blade plays a crucial role in controlling it, executing various techniques, and providing defense when parrying or blocking an opponent’s attack.

Fingering the Ricasso

The ricasso allows wrapping the index finger around the blade over the crossguard for greater tip control. This technique is often referred to as fingering the ricasso. Instead of fully wrapping around the ricasso, it is possible that the finger is only extended to slightly loosen the grip during a strike, which optimizes the force and effectiveness of impact. It is common on many bastard swords, cut-and-thrust swords, later rapiers, and smallswords.

Grabbing the Ricasso by Entire Hand

On two-handed swords, the ricasso is sometimes referred to as the false grip. It usually allows the entire second hand to securely grip and maintain control of the weapon. These swords were well-balanced for broad, sweeping blows. Still, the technique can shorten the blade’s length to increase maneuverability.

Receiving the Strike on the Ricasso

In longswords, the opponent’s oncoming strike can be received on the ricasso, flat of the blade, or crossguard while closing in—not on the sharp cutting edge. In some cases, it can be received on the flat of the ricasso.

However, later 18th and 19th-century fencing styles—particularly with the saber, cutlass, broadsword, and spadroon—taught blocking with the edge of the ricasso. For this reason, the ricasso’s edges were often made extra thick. Also, trapping or binding the opponent’s blade can be executed by pressing it against another, typically edge-to-edge contact at the ricasso.

Facts About the Ricasso

The ricasso is a characteristic feature commonly found in European swords and daggers. Still, it can be seen in bladed weapons of other cultures, such as sabers and curved daggers.

- European medieval swords can be classified based on their blade characteristics.

The sword typology of Ewart Oakeshott examines the blade—including the blade length, cross-section, fullers, tang shapes, and ricasso—as well as the crossguard style and pommel forms. For example, the Type XVIIIe swords are unique for their unusually narrow ricasso. On the other hand, the Type XIX swords have short ricasso with grooves.

- The ricasso of the German zweihander, or two-handed sword, can be grabbed by an entire hand.

The zweihander was primarily designed as a breaching weapon in pike formations. Its extra-long ricasso allowed the blade to be safely gripped below the quillons and wielded more effectively. Also, the zweihander has two parrying lugs called parierhaken, which function as a secondary handguard above the ricasso. These hooks also help prevent other weapons from sliding down the hand.

- Some rapiers had relatively thick and long ricasso.

The extra thick and long ricasso on rapiers helps in effectively parrying the strikes of broader-bladed swords. Generally, rapiers are gripped using point control, enabling accurate thrusting rather than edge control for powerful cutting. Sometimes, a wielder may grip the rapier by its pommel to extend its reach.

- European smallswords typically had a ricasso with small finger rings.

The smallswords, developed from the rapier, became the popular dueling sword towards the end of the 17th century. The proper handling of the weapon involves pinching the ricasso with the thumb and forefinger for better control of the tip instead of wrapping the index finger around. As a result, the smallswords had smaller finger rings—too small for the finger to pass through—than those of the rapier.

- The federschwert is recognized for its winged or flared ricasso.

The federschwert, also called feder, is a training sword used in Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA). It is mainly used to study longsword techniques and sometimes to practice arming sword techniques. It has a flared ricasso, though its metal blade is designed to bend when thrusting an opponent.

- Some European parrying daggers feature a ricasso.

In the early 16th century, parrying daggers accompanied rapiers and were held in the left hand. These left-hand daggers were used to ward off an attack until rapiers became practical for both attacking and defending.

In southern Italy and Spain, parrying daggers, also called main gauche daggers, remained popular until the 18th century. On parrying daggers, the ricasso enables the placement of the thumb on the back side of the blade, as required by certain fencing schools that emphasize specific techniques.

- Indian swords often have a ricasso with silver or gold overlay.

The characteristic sword of India, the talwar, often has a ricasso decorated with gold inlay or overlay called koftgari. These decorations are in the form of geometric borders, pairs of birds, and flowers. Also called koft, the koftgari (کوفت گری) is believed to have originated from Persia and later spread to India. Among many sword connoisseurs today, the term mainly refers to a type of overlay over a cross hatched background.

- Some Chinese straight swords, or jian, featured a ricasso.

The Chinese jian has a straight, double-edged blade. However, the ricasso is a later addition, appearing during the late Qing dynasty onwards and reflects European influence. In fact, the absence of a ricasso on the base of a blade is a more classic feature of the fighting jian. During the formative period of traditional Chinese martial arts, specifically the Republican period spanning from 1912 to 1949, it is worth noting that the jian often lacked a ricasso.

- Some ricasso on daggers is held by langets.

Some katar daggers had curved blades, which were popular around the 16th and 17th centuries. Their curved blades featured a ricasso and secondary bevels forming the edge. Unlike other daggers, the blade is riveted to thick langets or metal plates, which are decoratively chiseled.