Hamon in a Katana Sword: The Pattern of the Hardened Edge

What’s in this article?

One of the most remarkable features of a katana or any Japanese blade is the hamon, the visible pattern of the hardened steel along the cutting edge. Giving the blade its superior cutting ability and artistic qualities, the hamon is a good indicator of a swordsmith’s skill level. Several hamon patterns are associated with swordmaking schools, provinces, and trends of various periods.

Let’s explore the characteristics of a hamon, its various types, patterns, purpose, and the features of a good hamon.

What Exactly Is a Hamon?

The Japanese term hamon (刃文) literally means blade pattern. A swordsmith hardens the steel at the cutting edge when a Katana is made. This unique hardening process creates a wavy line called hamon. It indicates that the cutting edge has been hardened far greater than the rest of the blade, making it suitable for effective cutting.

A traditionally-made Japanese sword must always have a hamon. A properly designed hamon limits the damage the cutting edge suffers during use. It also has an artistic value and a skilled swordsmith can produce a wide variety of hamon patterns such as a series of arcs, clouds, waves, zigzags, or anything in between.

Characteristics of the Hamon

A hamon generally has a different color from the body of the blade. However, many fine details can be seen when examining the hamon.

Here are the characteristics of the hamon and a few terminologies used to describe its features:

Structure and Composition

The primary function of a hamon is to create a blade with a very hard cutting edge on a tougher body. Generally, steel hardens by heating and rapid cooling. Hardened steel can be sharpened, but it can be too brittle for the blade’s body. Japanese swordsmiths developed techniques for hardening only the blade’s cutting edge, leaving the body more flexible.

When a Japanese sword is heat-treated, it produces a hamon, a visible boundary line between the hardened steel in the edge area and the softer blade’s body. A real hamon is typically formed by differential hardening treatment, unlike fake ones that were only acid-etched or stenciled on the blade surface.

Appearance of the Hamon

A hamon generally has a whitish or grayish color. In proper lighting conditions, a hamon may light up brightly. It does not have just a simple shape but also contains complex patterns and details. These include the nioi and nie, habuchi, ashi, and boshi, to name a few.

Nioi (Fine Particles)

The nioi has a misty appearance, like sparkling diamond powder in the hamon. Too small to see individually, there are no dots or large crystal particles visible. All Japanese swords have nioi along the hamon.

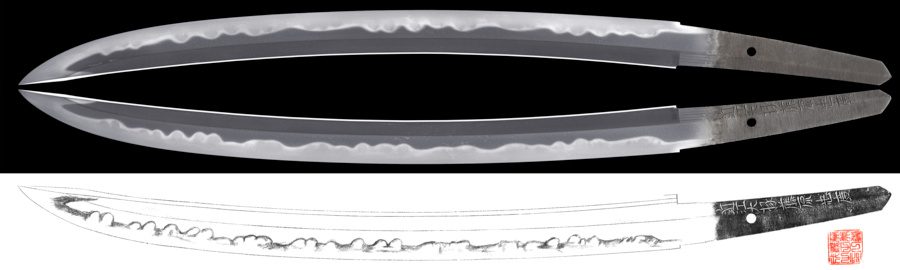

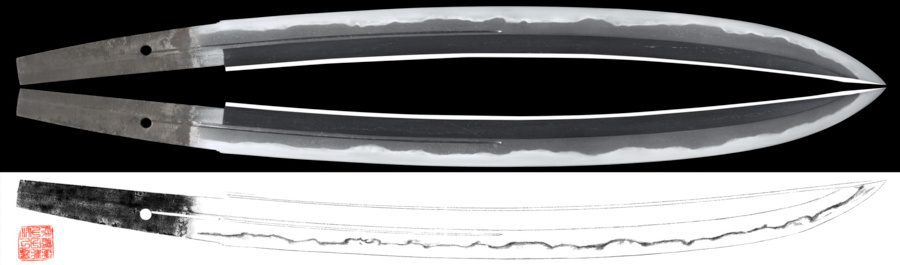

The term nioi (匂) means fragrance. When the hamon shows nioi throughout—with little or without separate dots or particles (nie)—it is called nioi deki. The term deki simply means workmanship or interpretation.

Nie (Large Crystals)

The nie refers to the single, large martensite crystals that appear as separate dots or islands. It is mostly seen along the hamon or above it. Very large nie particles are called ara-nie, while very small dots are called ko-nie.

The term nie (沸) means boil, a reference to its appearance of looking like bubbles of boiling water rising to the surface. The term nie-deki means that the hamon features visible grainy nie particles. However, the presence of nie is more associated with the swordmaking tradition, such as the Sōshū school, rather than quality.

Habuchi (Border of the Hamon)

The habuchi is the border of the hamon—the region where the hardened edge and the body of the blade meets. The habuchi is sometimes called nioiguchi, as the nioi is always present at the border of a hamon.

A good hamon will always have a bright, clear border (habuchi) that sets it off against the blade’s body. The boundary line should have no gaps, breaks, or unnatural width and brightness. It must be present throughout the blade, without weak or faded areas.

Ashi (Extending Lines)

A hamon often has lines extending towards the cutting edge. These extensions or projections are called ashi (足). These lines were originally designed to limit the size of chips on the cutting edge, preventing them from spreading laterally. As long as they are present and the hamon itself is unbroken, any hamon pattern will be equally effective for a good sword.

Boshi (Hamon of the Point)

A hamon should be present along the entire length of the blade, including the point. The hamon of the point (kissaki) is called boshi, meaning hat. The boshi has various shapes and patterns. Generally, it should be very clear, and the kissaki should have a uniform white appearance.

Types of Hamon Patterns

There are various hamon patterns and the complex ones developed in response to the need for hard, sharp, and functional swords. The two main types of hamon are straight and irregular patterns. In most cases, a blade features mixed hamon patterns.

1. Suguha (Straight)

Suguha is a generic term for a straight hamon. It runs parallel to the cutting edge and may vary in width. It may be classified as hiro-suguha (wide), chu-suguha (medium), or hoso-suguha (narrow). An extremely narrow suguha is called ito (string) suguha.

2. Midareba (Irregular)

All hamon other than suguha (straight) can be considered midareba. It may be classified based on its irregularity: small irregularities (ko-midare) or large irregularities (o-midare). However, there is a wide variety of irregular hamon, many of which have their own names.

3. Gunome (Waves)

A gunome hamon is recognized for its regular wavy pattern or semicircular waves. It generally has the same width at the base and top of the wave. Depending on its size, it may be called ko-gunome (small) or o-gunome (large).

Various other types of gunome hamon are also referred to by their respective shapes. The togari gunome is a gunome in which the peaks are pointed and orderly, while the sanbon-sugi resembles a cluster of three cedar trees. It can be mixed midareba and then is called gunome midare.

4. Notare (Irregular and Undulating)

The outline of the notare hamon is irregular and undulating, featuring elongated waves. Depending on the amplitude of the waves, they can be classified as ko-notare (small) or o-notare (large). If a hamon is composed of entirely notare waves, it is called notare-ba, which features waves that swell towards and away from the cutting edge in an irregular pattern.

5. Choji (Clove Flowers)

The choji hamon is made to look like clove buds (choji) and comes in many variations. Generally, it is an irregular hamon and its clove patterns can range from small to large, regularly waved, and irregularly wavy. Double or multiple choji clustered together is called juka choji. Sometimes, a choji wave resembles the shape of a tadpole (kawazuko) when viewed from above and is called kawazuko choji.

6. Sudareba (Bamboo Curtain)

Sudare is a bamboo-strip blind, similar to the pattern inside the hamon. The sudareba hamon may be based on suguha (straight) or shallow notare (elongated waves). It resembles the multiple parallel lines running parallel to the cutting edge.

7. Toranba (Large Waves)

The toranba hamon features large, surging waves that form deep valleys and high peaks. Sometimes, it features a rounded tempered spot called tama (jewel), separate from the main hamon.

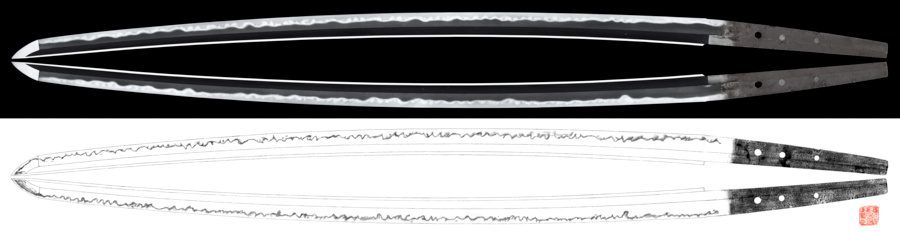

8. Hitatsura (Mottled)

The term hitatsura literally means everything hardened. Most recognized for its wild and untamed look, the hitatsura hamon features scattered patches and spots of hardened steel throughout the blade in addition to normal hamon.

Making the Hamon

Creating a hamon is a delicate and complex process. It is traditionally achieved by covering the blade in clay, heating it, and then quenching it in water. Lastly, the hamon is hand polished to stand out from the rest of the blade.

Tsuchioki: Applying Clay to the Blade

Making the hamon by coating the blade with clay is called tsuchioki. After forging, clay is applied to the blade before it is heated and quenched. The clay pattern can be very detailed and affect the final look of the hamon. The clay is applied thicker along the blade’s back (mune) and upper body to cool slower while a thinner layer is coated on the to allow it to cool faster.

Yaki-ire: Hardening the Edge

The process of forming the hamon by heating and cooling the blade by plunging it into water is called yaki-ire. When done correctly, it alters the crystal structure of the steel in the edge, producing the hamon.

The hamon is composed of a crystal structure called martensite, formed by the sudden cooling of high-carbon steel. The crystalline structures (martensite) come in two main types: nioi and nie. They are identical from a metallurgical point of view but differ in appearance.

Hadaka-yaki: Making a Hamon without a Clay Coating

The hadaka-yaki is the oldest way of creating a hamon. The final hamon depends on the carbon content in the steel, how the blade’s surface is prepared, and the specific temperature the blade is heated before quenching. However, it does not show the swordsmith’s style as clearly as the tsuchioki.

Polishing the Hamon

The polisher brings out all the essential features of the sword’s surface, including the hamon, jigane, and jihada. There are two types of finish: the sashikomi and the hadori. The effect of the sashikomi is subdued, while the hadori polish brightens the outline of the hamon.

History of the Hamon

The Japanese swordsmiths took about five hundred years from making the earliest basic hamon to the complex hamon we know today.

In the Asuka Period (552 – 645)

The oldest Japanese swords, dating from around the 5th or 6th centuries, were straight, thin, and seemed impractical for combat. Japanese swordsmiths began using clay to create the hamon, though it generally lacked strength and clarity.

Swords had a simple, straight hamon, consisting of a hard martensite steel bonded with a softer steel body. Due to the differences in steel properties, a single blow could cause the cutting edge to separate from the sword’s body.

The sword owned by Prince Taishi Shōtoku had a katakiriha-zukuri blade shape and a narrow, almost straight hamon. Some Heian-period tachi swords had a complex yet narrow hamon along their entire length.

In the Heian Period (794 – 1185)

The Japanese sword evolved by the mid-Heian period as blades became larger, longer, and curved. By the end of the period, wider and more complex hamon emerged. Some hamon resembled a series of teeth, limiting the damage and the size of chips that can occur in the cutting edge during use. The blades also featured the modern point with a hamon called boshi.

In the Kamakura Period (1192 – 1333)

By the 12th century, the samurai class gained much power and influence, which resulted in a demand for efficient swords. The sword design acquired more curvature and added a soft iron core into the center of the blade. Early Kamakura-period-tachi had well-defined gunome or choji hamon patterns.

By the end of the Kamakura period, the Gokaden school, the five major swordmaking traditions, developed in Japan. Each school developed efficient swords with its distinctive hamon. The Gokaden traditions remained strong through the early Muromachi period, from 1338 to 1573. In fact, modern Japanese swords today are modeled on Kamakura-period swords.

In the Meiji Period (1868 – 1912)

The great demand of the Japanese military for swords resulted in the mass production of blades. Modern machines forged these swords, and the hamon was made by quenching the blades in oil instead of water. These swords were sometimes called Muratato (Murata swords), honoring one of the founders of the modern Japanese military forces.

In the Showa Period (1926 – 1989)

Showa-to refers to the swords made during the Showa period, especially in the 1930s. Showa-period swords had blades made from modern foundry steel instead of the tamahagane. Some may also feature a hamon, but its quality differs from traditional Japanese swords made from tamahagane. Also, Showa-to lacks the characteristic steel surface and jihada pattern.

Facts About the Hamon

There can be at least fifty different hamon, each with its own name. Often, specific hamon patterns are associated with sword making traditions or particular schools.

A properly-made, complex hamon can serve as the fingerprint of a swordsmith.

Making a hamon is a complex process; a swordsmith needs years of training to master it. No two smiths create it exactly the same way. There are several smiths or groups of smiths whose work can be identified from their hamon alone.

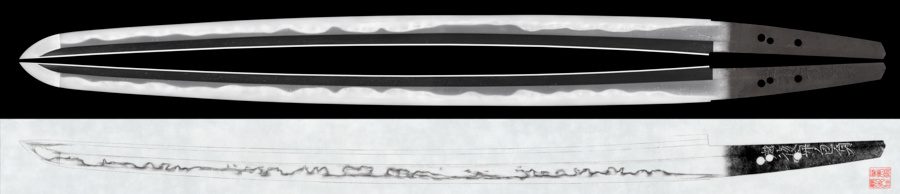

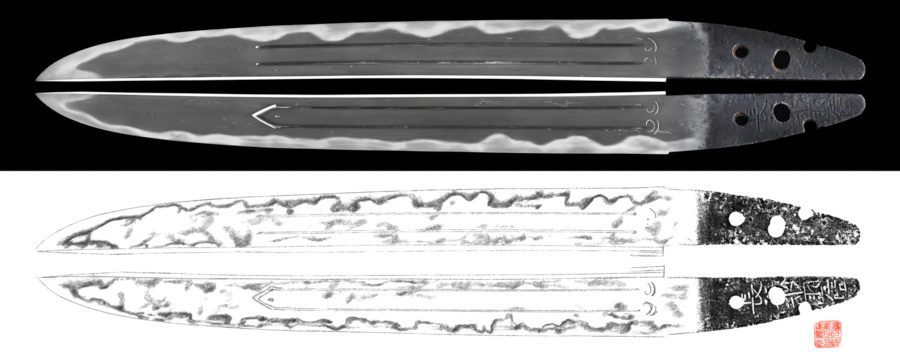

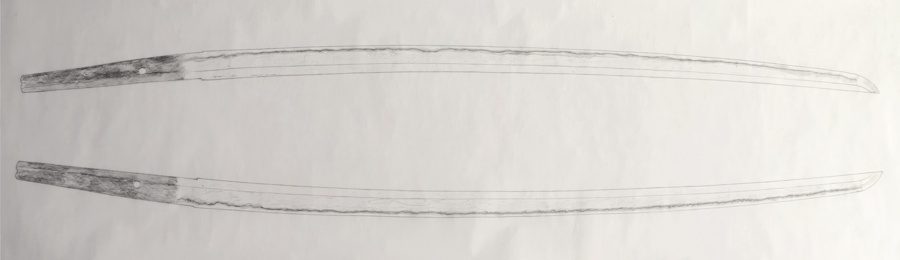

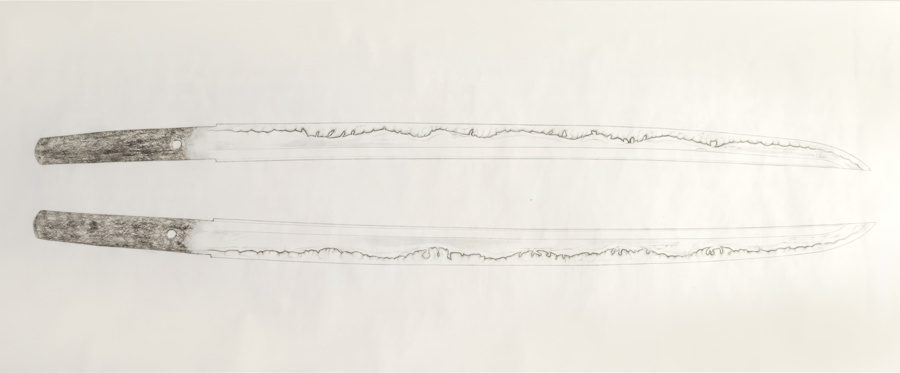

The oshigata drawing of a blade includes the fine details of a hamon.

Photographs of sword blades only show the hamon outlines, but the fine details are not visible. An oshigata is an accurate drawing of the blade, showing the hamon with its intricate and complex details. The oshigata also includes the shape and form of the blade, smith’s signature on the tang, and hard-to-distinguish features on the steel blade. It helps in identifying a sword to a smith or school.

A hamon may be named based on its distinctive shape.

The kani no tsume literally means crab claws. It is also a special gunome-midare hamon with alternate protrusions to the left and right, reminding us of crab claws. However, the name kani no tsume often applies to Sue-Bizen blades. If the same feature is described on Sue-Seki blades, it is called kani no te, meaning crab hands.

The Japanese term hamon is widely referred to in the West as the temper line.

In the West, the hardening of Japanese swords is often described as tempering, often clay tempering, and the hamon is referred to as the temper line. However, these can be inaccurate, as tempering is done after the hardening to make the steel less brittle. Technically, it is more accurate to say that the Japanese blade is heat-treated to harden the cutting edge.

Japanese sword making is unique—and the term temper line seems to be the most widely used term to describe the hamon‘s function without delving into the whole process of making it. Some Japanese sources refer to the hamon as the pattern of the hardened edge or hardening mark.

A traditionally-made Japanese blade has a structure composed of various types of steel.

A Japanese blade has a softer steel core (shingane) at its center, functioning as a shock absorber to prevent the blade from fracturing. It also has a hard, high-carbon steel jacket (kawagane) that forms the blade’s surface. Then, it has the hamon, the hardened edge formed of martensite, a very hard steel, which is far harder than the steel in the blade’s body.

Making a Japanese sword is a long, complex process.

After a polisher brings out all the details of the steel surface, the blade goes to a craftsman who makes the habaki blade collar. Then, it goes to a scabbard (saya) maker for a shirasaya, or a traditional koshirae—a complete functional mounting with a lacquered scabbard, sword guard (tsuba), a tsuka wrapped in ray skin, and other metal fittings.

Other bladed weapons, like polearms, had a hamon.

A hamon is widely seen on the Japanese katana sword, wakizashi, and tanto dagger. It can also appear in other bladed weapons, like the naginata and yari. However, the hamon on a yari blade is usually straight and tight, as it cannot be easy with a complex-shaped object.

Conclusion

The hamon is the visible, hardened edge of the Japanese sword, unseen among other swords in the world. Initially purely functional, it was designed to create very hard cutting edges, but it soon became an art form. The hamon remains one of the most critical factors in evaluating Japanese swords.